The modern practice of “historical fencing” is difficult to define. While the debate about what constitutes historical fencing will certainly never end, most definitions include at least a couple of the following characteristics:

- Fencing with weapon simulators designed to closely replicate historical weapons

- Reconstructing a fencing tradition from written historical sources for which there is no living tradition

- Fencing according to a certain documented historical fencing tradition

- Fencing as a martial art in addition to (or instead of) as a martial sport

In the historical periods we study, what we now call “historical fencing” was, of course, just “fencing”. We have “fencing” today too in the form of modern Olympic fencing, Kendo, Eskrima, and many others, but – since hand-to-hand combat with bladed weapons is essentially irrelevant in the 21st century – most of these traditions are practiced in sportified forms. While fencing for fun has existed for as long as fencing has existed, many historical fencing sources focus on fighting in earnest (that is, a fight with sharp swords where both participants are willing to inflict potentially grievous injuries on the other).

Most people agree that genuine risk to life and limb adds an entirely different dimension to fencing which does not exist in a sportive context. Most people also agree that martial sports of all kinds (fencing, boxing, wrestling and so on) teach skills that are applicable to “real fights” (whatever that means!). However, a frequent point of debate is to what extent martial sports fall short of preparing their participants for a “Real Fight™” .

I’d like to offer a framework for discussing this question. For the sake of this discussion, I’ll only be considering modern Olympic fencing vs historical fencing, but this framework could equally apply to any martial sport compared to a martial art.

Strategy > Tactics > Techniques > Actions

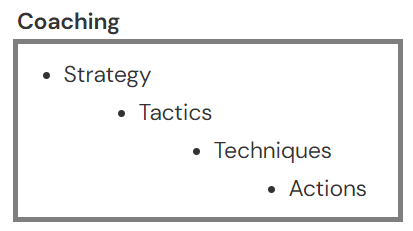

I like to divide fencing into four levels:

- Strategy

- Tactics

- Techniques

- Actions

- Techniques

- Tactics

Actions are individual motions; “the smallest unit of fencing”:

- Advance

- Retreat

- Lunge

- Pass

- Extend your arm

- Retract your arm

- Inside parry

- Outside parry

- Engage your opponent’s blade

- Disengage around your opponent’s blade

- Thrust

- And so on…

Techniques result from linking individual actions in a meaningful way:

- Conservative direct attack

- Committed direct attack

- Indirect attack

- Parry + Riposte

- Extend + Disengage + Thrust

- Extend + Retract + Attack

- Counterattack with opposition

- And so on…

Tactics are mini-goals that can be achieved through diverse techniques:

- Overwhelm them with committed attacks

- Keep them at a distance and make conservative attacks

- Crush distance and grapple

- Provoke a predictable response and exploit that response

- Lure them into an attack on prep

- Wait for them to come to you

- Bait them into attacking

- Remain calm

- And so on…

Strategy is the overarching goal that your tactics serve:

- Hit them at any cost

- Hit without being hit

- Put on a good show

- Run out the clock

- Survive

- Challenge them, but let them win sometimes

- Embarrass them in front of their friends

- Make them look good in front of their friends

- And so on…

Actions and techniques are drilled into memory through many hours of practice. As such, the quality of an individual action or technique is determined mostly by the amount of time spent refining it (and the fundamental usefulness of the technique; cartwheels, for example, are probably not a super useful technique for any kind of fencing).

Tactics and strategy, by contrast, are the product of (or at least strongly influenced by) conscious decision making. How I form my inside parry may be mostly trained instinct, but I can still choose not to parry, for example.

Wrapped around this hierarchy is the teaching methodology. The quality of coaching influences how successfully the ideas are transferred to the learner:

Getting caught up in the details

I think this framework is illuminating because it draws attention to the border between the physical and the mental components of fencing.

In my experience in the historical fencing community, a huge amount of time is invested in talking about how to stand, how to step, how to parry, and how to attack in myriad different ways. That is, a huge emphasis on actions and techniques. A solid grasp of such fundamentals is necessary, but I would argue that postures, movements and techniques are the least interesting part of fencing and that “fencing” only begins once these fundamentals are familiar enough that you don’t need to actively think about them to use them. Put another way, actions are not the hard part of fencing.

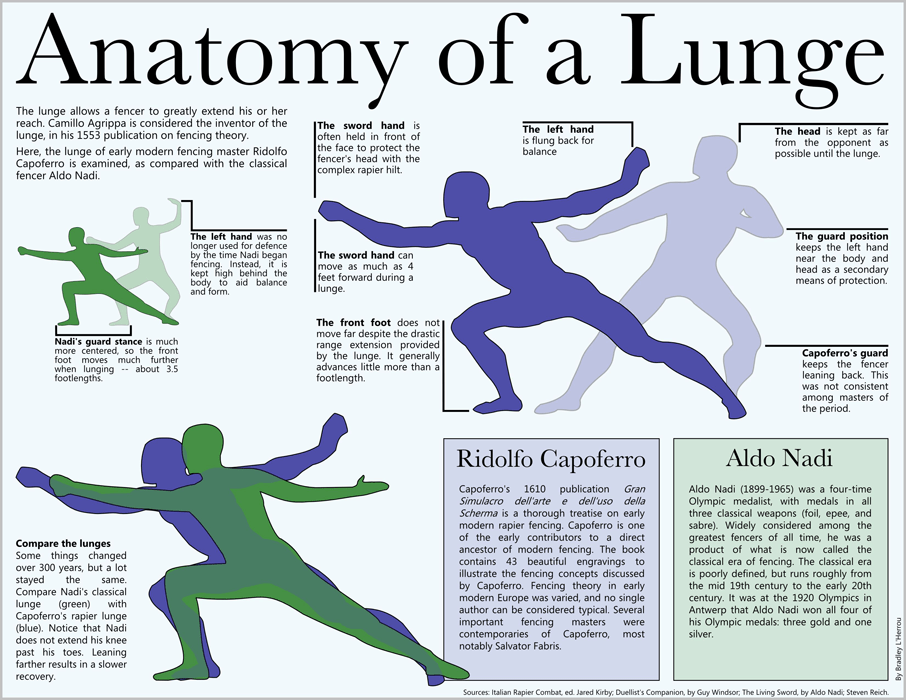

This emphasis on actions translates into an emphasis on comparing actions when contrasting historical fencing to sport fencing. For example, discussions comparing the lunge in various historical sources to the lunge in modern fencing focus on how the sport fencing lunge is long and committed, whereas most historical sources advise the fencer to make a smaller lunge so that they can recover to guard more quickly. While these observations are accurate, the discussion often ends there. This can give the false impression that the sport fencer is, somehow, unaware of the fact that a very long lunge is harder to recover from or that the sport fencer doesn’t know more conservative ways of attacking.

The differences in pedagogy shouldn’t be ignored either. Modern sport fencing coaches will incorporate the latest insights from sports science and medicine into their training whereas incorporating modern ideas about how to teach and how to train may be outright antithetical to certain conceptions of “historical” fencing.

Modern Épée Fencing vs 18th Century Smallsword

So, what are the relevant differences between modern Olympic fencing and historical fencing?

Let’s compare two disciplines that are reasonably similar. Obviously, an épée fencer who has never held a two-handed sword will be ignorant of many of the actions associated with the two-handed sword. If a fencer lacks the ability to perform basic actions at will, obviously they will struggle to fence.

If we compare modern épée fencing to 18th century smallsword fencing, by contrast, we see that the actions and techniques not very different. Yes, there are some techniques which exist in the one discipline and not in the other, but the fundamentals are very similar.

Similarly, there are no tactics in the two disciplines that are wholly unique to either modern épée or 18th century smallsword, so – even if the most common tactical preferences are different – neither discipline would be in the dark about what the other is trying to do.

The strategy, however, while dueling is certainly going to be different from fencing in a sportive environment. For example, in a duel…

- a fencer may place higher value on not being hit and, therefore, opt for more conservative tactics

- a fencer may place a higher value on hitting their opponent due to an emotional investment in defeating their opponent and, therefore, keep going at any cost

- a fencer may avoid attacking certain targets – such as the foot – because hitting them would be largely ineffectual and yet dangerous

- a fencer may incorporate the terrain into their tactics differently

However, as argued earlier, strategy exists at the conscious level of decision making. As such, an experienced fencer should be able to adjust their approach for the situation at hand. Indeed, sport fencers already do this all the time in competition: a fencer who is down by 3 touches needs to adopt a different strategy than a fencer who is leading by 3 touches. As long as the fencer has a good grasp of the actions, techniques, and tactics necessary to pursue their strategy, this shift shouldn’t pose too big a problem.

So, the next question is who is better at implementing their strategy? The sport fencer or the historical fencer? That depends on who has more experience using the actions, techniques, and tactics necessary to support that strategy.

Putting in the time

A common error I see many historical fencers make is to assume that because sport fencing prioritizes a different strategy, the sport fencer must necessarily have less experience training for whatever strategy the historical fencer considers more important. A naive example might be the claim:

“Sport fencing only focuses on the attack and neglects defense; in a real fight, a sport fencer would get themselves killed more often than not with their suicidal approach”

– a YouTube comment, probably

It is naive to assume that a trained sport fencer would approach a fight with sharp swords the same way they would approach a sportive bout at their local fencing club.

Many high-level sport fencers train 10-20 hours per week (plus strength and conditioning training). Even if they spend only a fraction of their time training conservative approaches, such a fencer is getting more experience each week than the average hobby historical fencer.

Of course, not all sport fencers put in that kind of time and a historical fencer who trains at the same level of intensity for a similar length of time (or at lower intensity but over a longer time) might perform similarly well (or better!), but – in a fight between a sport fencer who trains 20 hours per week and a hobby historical fencer who trains 3 hours per week – my money would be on the sport fencer.

There’s a cup of tea for everyone!

HEMA is diverse. And that’s a good thing! Sport fencing vs. historical fencing is kinda a meme within the community at this point. I think sport fencing and historical fencing are both awesome. It’s okay to say “such and such isn’t my cup of tea”, but let’s remember: at the end of the day, we’re all sword people 🙂

Leave a comment