Eine deutsche Version dieses Beitrags findest du hier.

Too long, didn’t read:

Blade grabs are historically attested. Grabbing a sharp blade is dangerous, but sometimes worth the risk. Robin Swords explains it really well in just 42 seconds in this video.

Is it possible to safely grab a sharp blade in a sword fight?

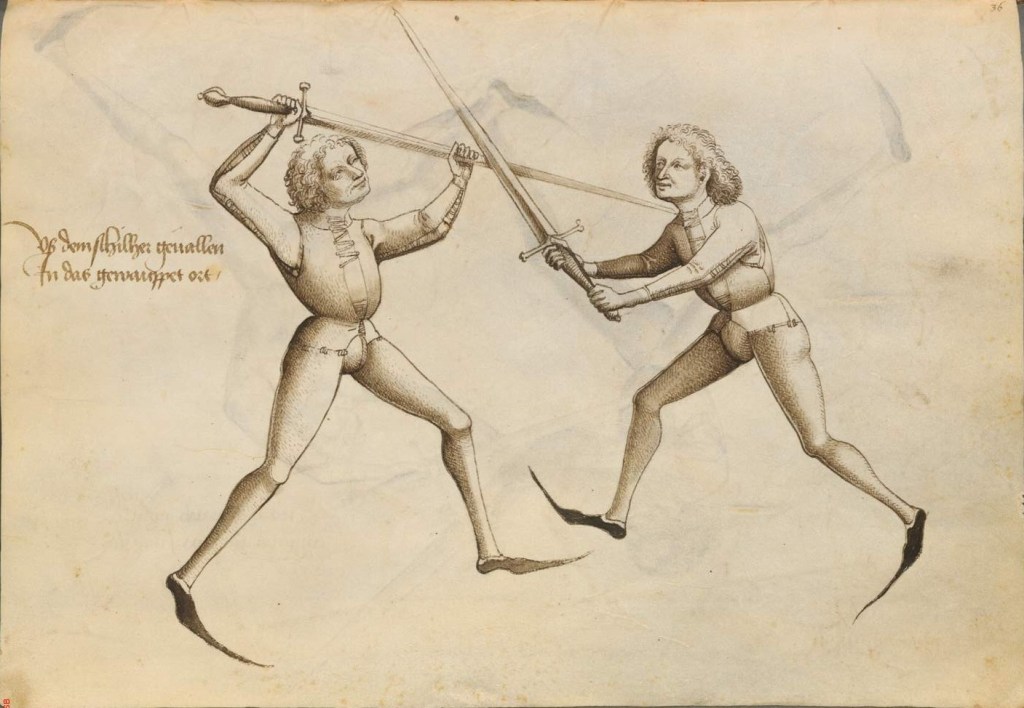

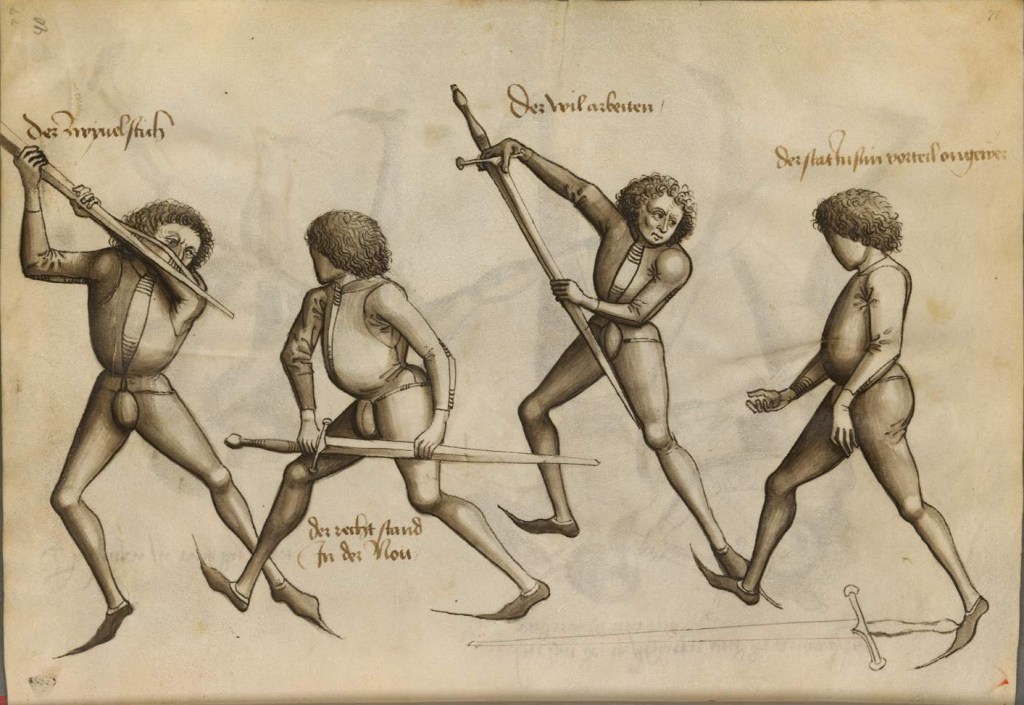

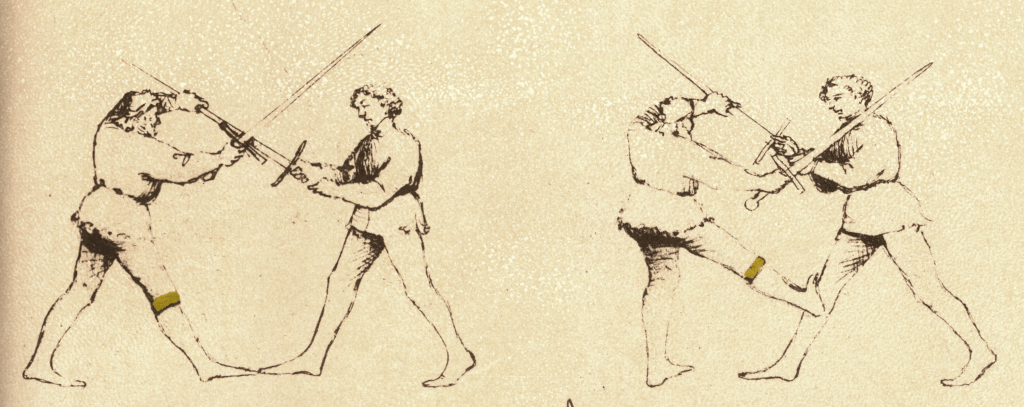

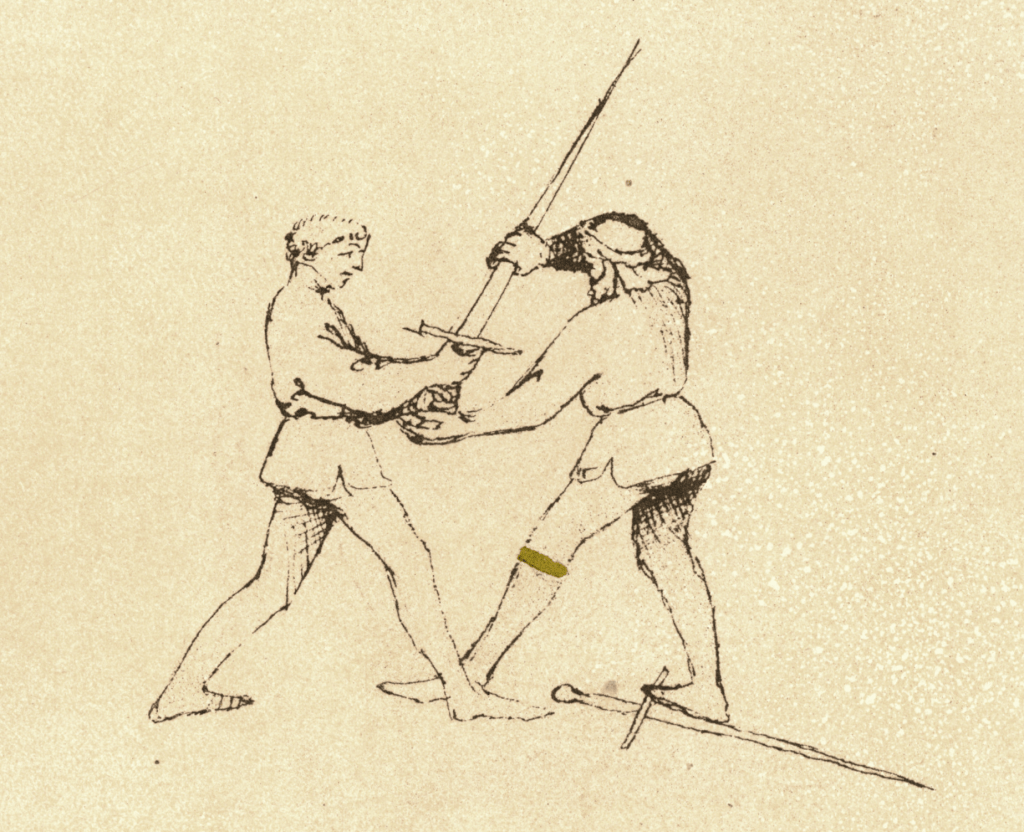

You might think the answer would be “obviously, no”, but then you might be surprised by the huge amount of artistic and textual evidence to the contrary. At least within European swordsmanship, people seem to have grabbed sharp blades a lot.

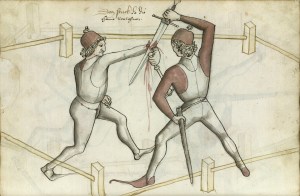

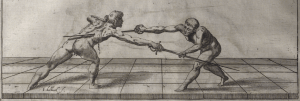

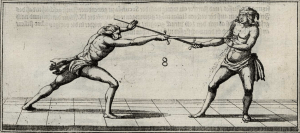

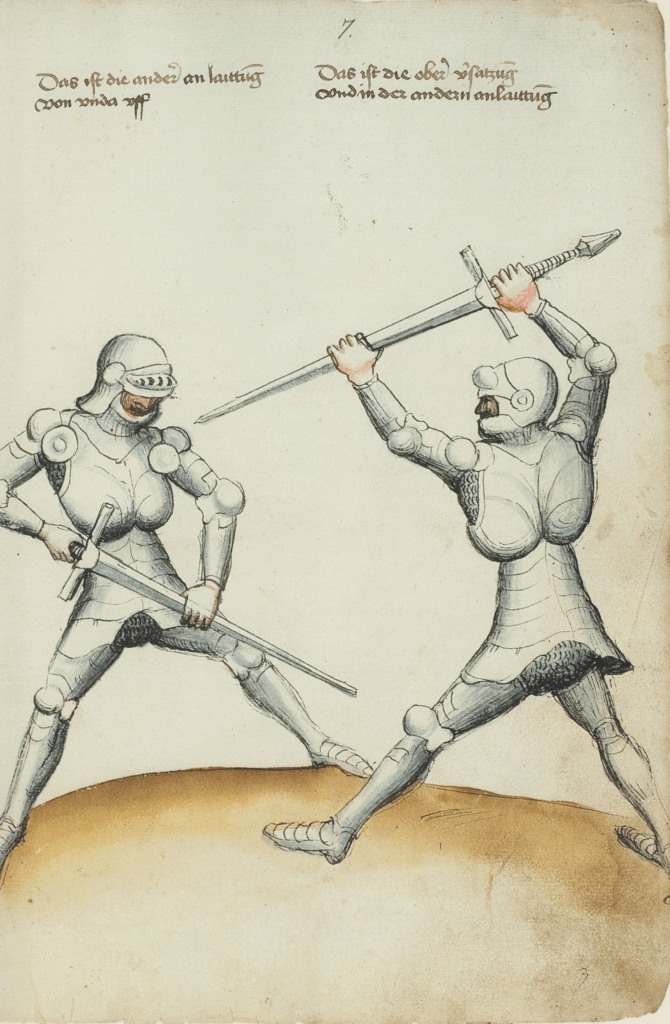

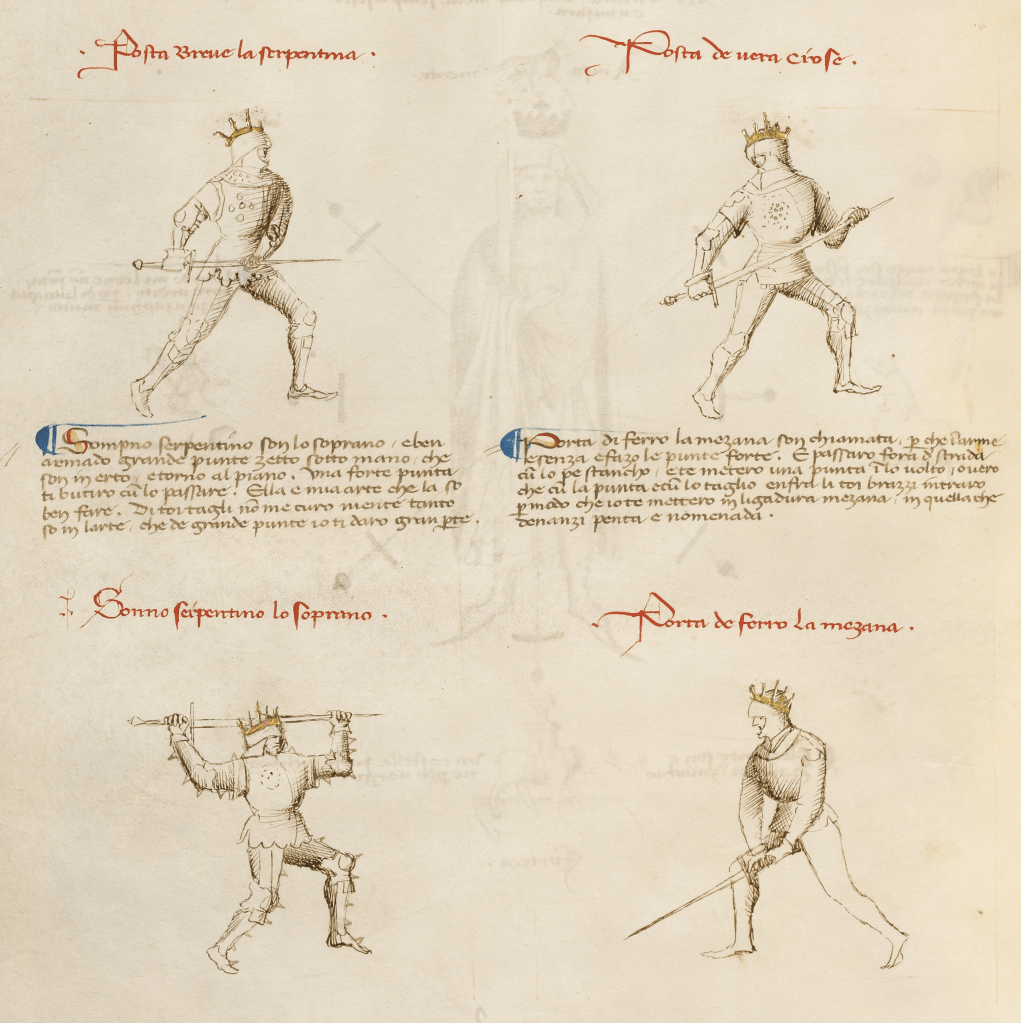

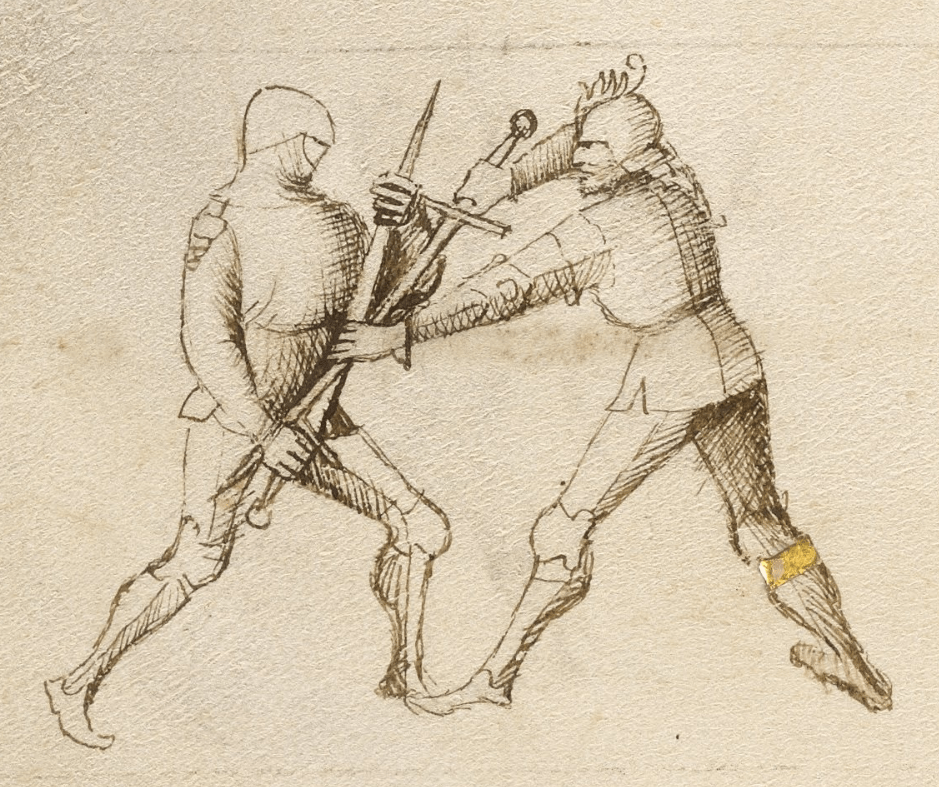

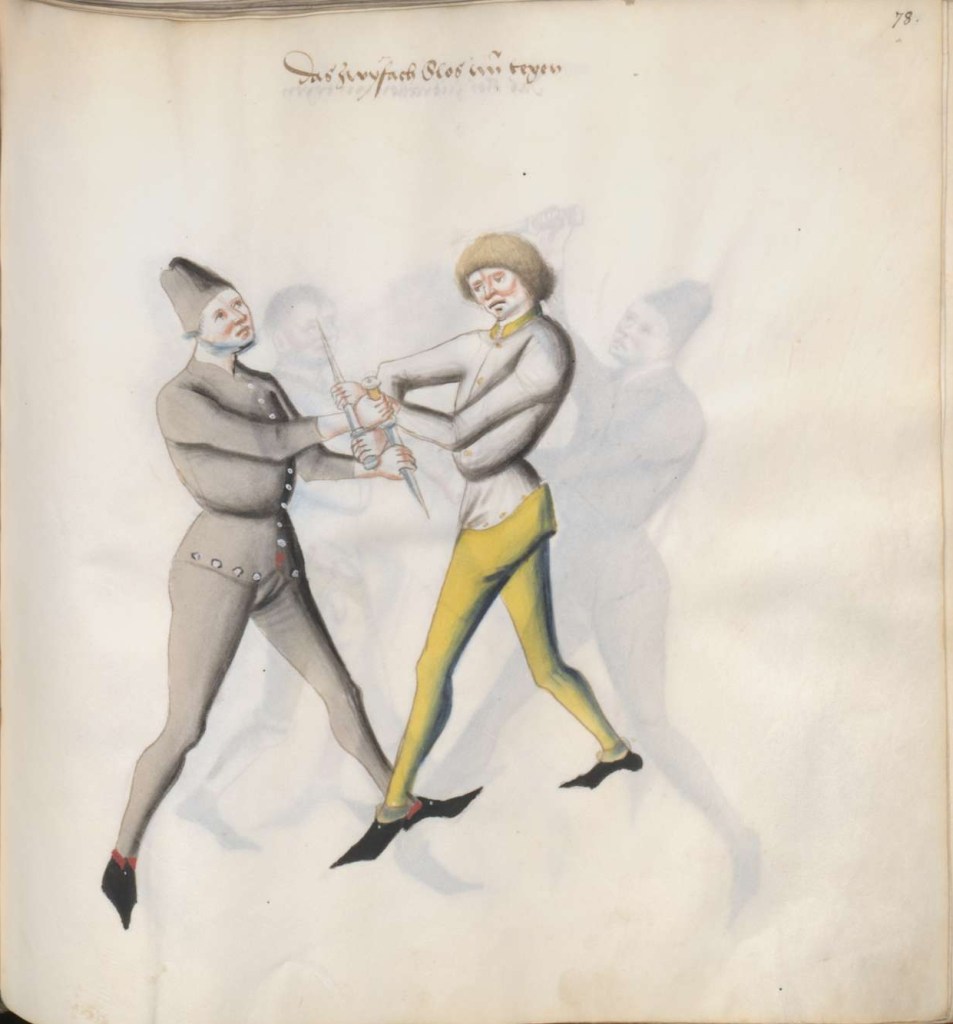

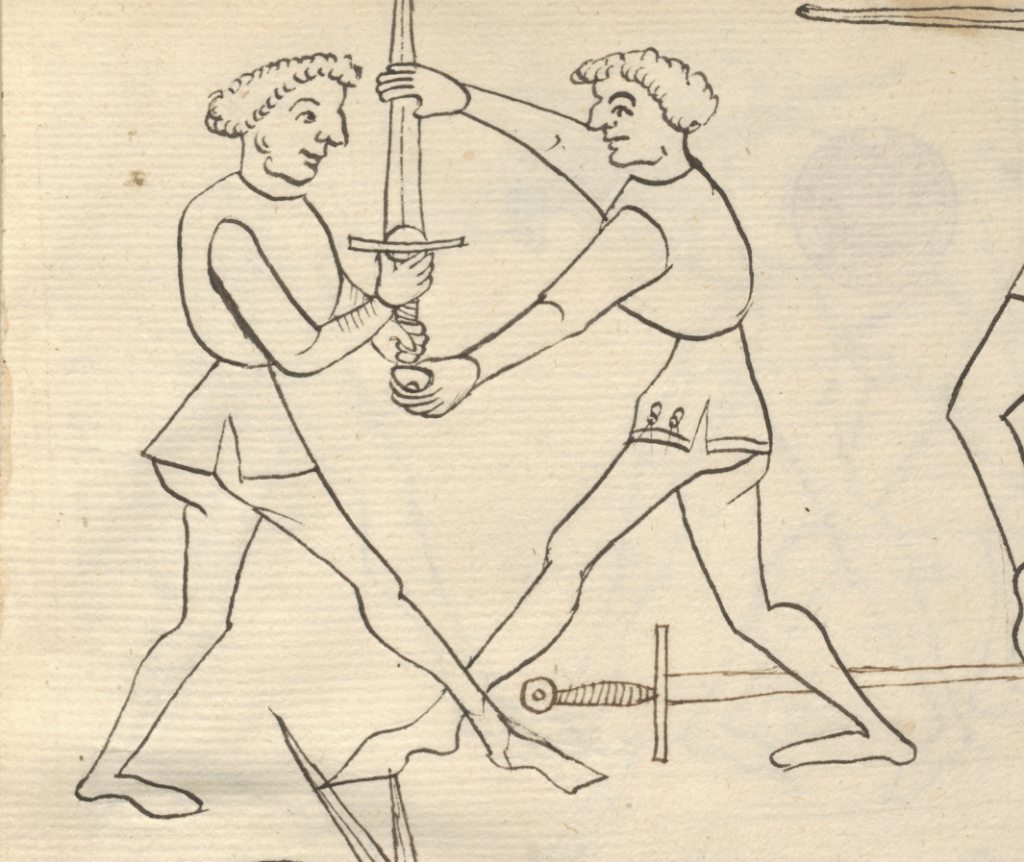

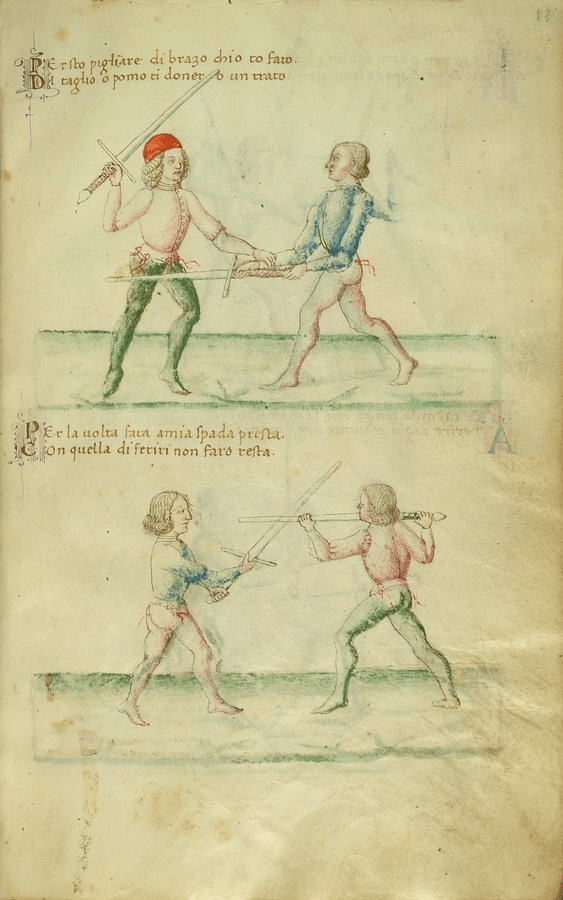

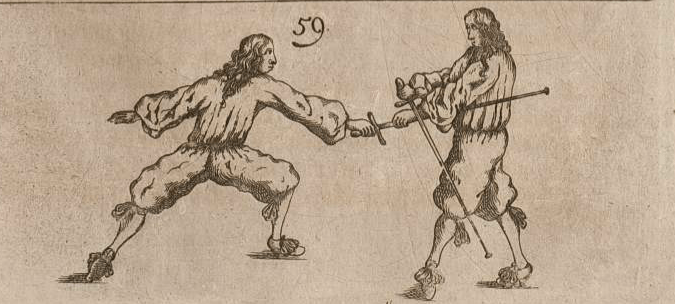

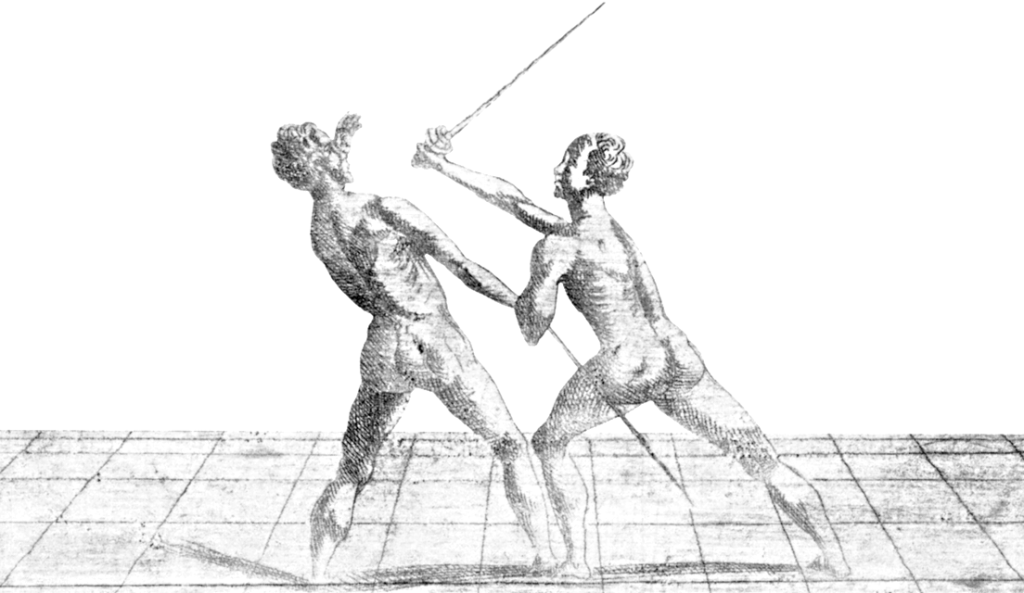

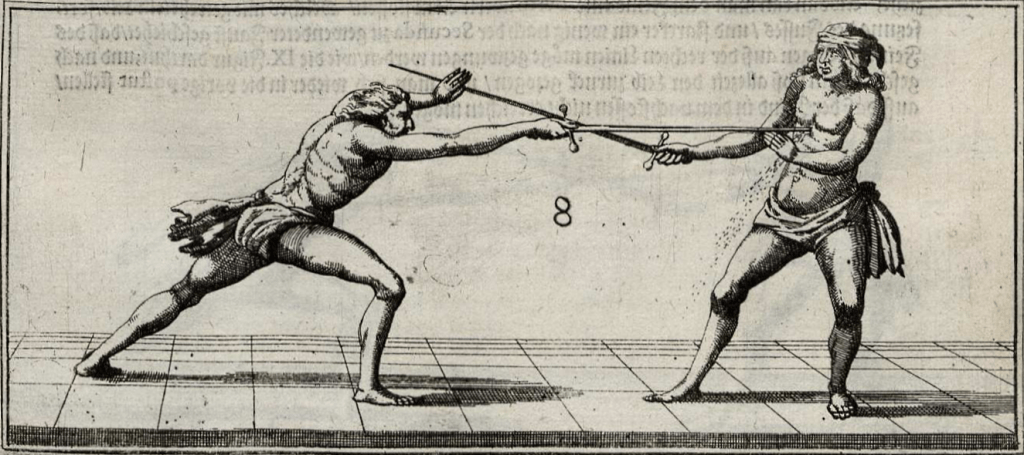

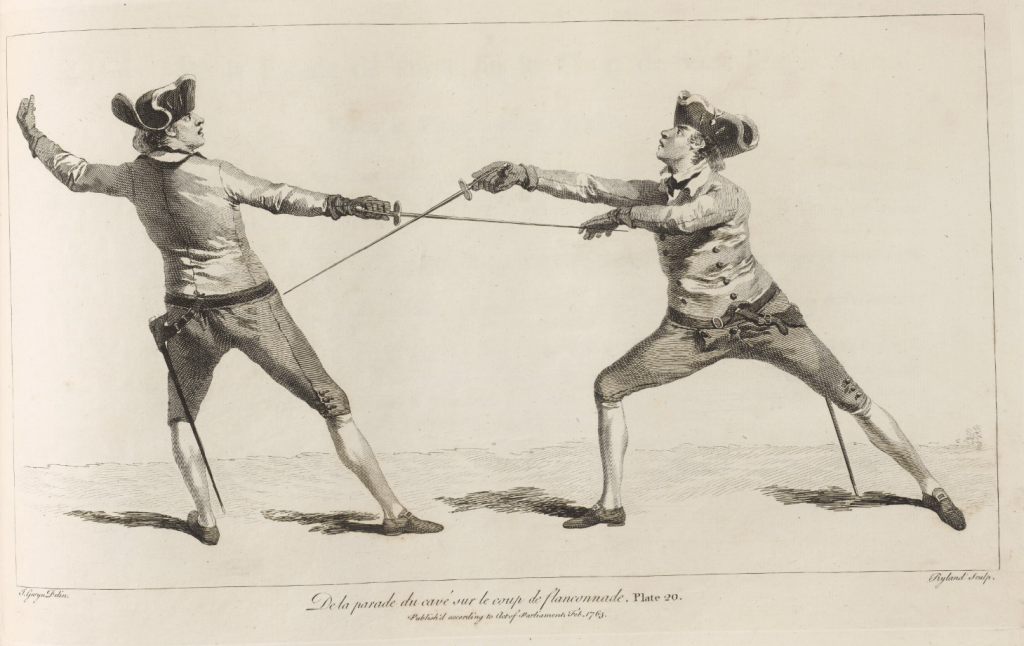

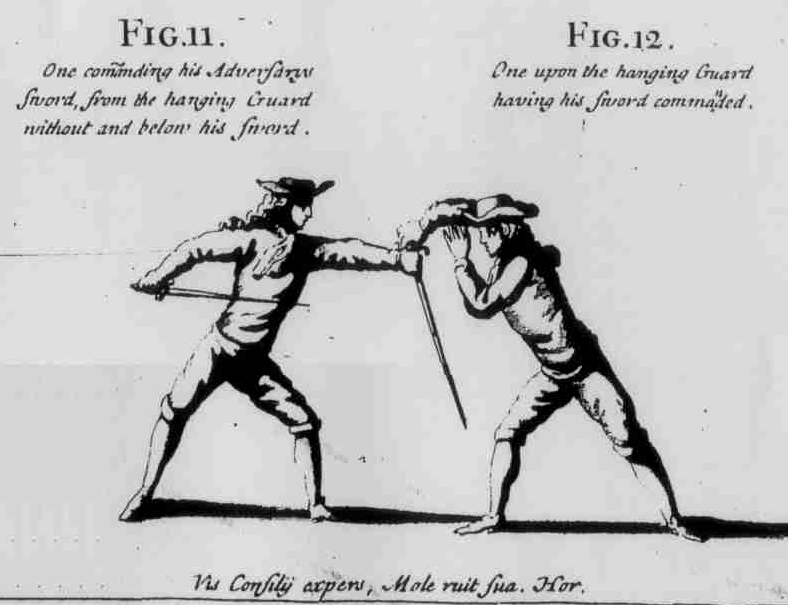

Here’s just a small sample of images from fencing treatises across the centuries featuring intentional contact between the blade and (often bare!) hands, both in armour and out of armour, with a variety of weapons:

Why are they doing that? Are they stupid?

Given the visual evidence, let’s look at some hypotheses for why we’re seeing what we’re seeing:

- “The fencing masters who recommended these techniques were stupid”

- My opinion? False.

- If only one or two fencing masters recommended blade grabs, we might be able to dismiss them as outliers, but that isn’t the case

- At least certain kinds of blade grabs are a staple of medieval European fencing; almost all surviving treatises from this era show grabbing one’s own sword or dagger blade, for example

- My opinion? False.

- “These techniques were intended only for fencing with blunt weapons and would never have been used in earnest against a sharp weapon”

- My opinion? False.

- In many cases the author explicitly states that their fencing is intended for fights with sharp weapons

- Sometimes the context of the fencing treatise is not explicitly stated, but the way in which a technique is illustrated or described suggests applicability to an earnest fight

- For example, if a blade grab is used to facilitate breaking your opponent’s arm, that probably isn’t intended for friendly competition

- There is some evidence that blade grabs and wrestling were often banned from sportive fencing competition outright, so it seems strange to have an emphasis on a class of techniques for sport that is often prohibited within sport

- My opinion? False.

- “Earlier swords and daggers weren’t that sharp; if it had been a later period sword (or a Japanese katana!!1!), such techniques would be impossible”

- My opinion? False.

- Could you shave with the edge on an average medieval sword or dagger? Maybe not. But that shouldn’t be the only standard for sharpness.

- While some swords are indeed sharper or better at cutting than others and certain swords and daggers specialized for thrusting have little or no cutting capacity, archaeological and artistic evidence suggests that – in general – medieval and Renaissance European swords and knives were sharp

- Even bronze age swords and knives were sharp! Medieval people were perfectly capable of making very sharp steel weapons

- Some videos on medieval sword sharpness:

- My opinion? False.

Although some specialized gloves featured chain-mail on the palm specifically to facilitate blade grabs, most historical gauntlets have no armour on the palm

- “These techniques were only ever done in armour”

- My opinion? False.

- Some historical techniques involving grabbing sword blades are, indeed, specialized for armoured combat, but many clearly aren’t

- Some such techniques are depicted without armour

- Sometimes the author explicitly tells us the technique can be done without armour

- Some such techniques would be superfluous if one were wearing armour

- Some people assume that armoured gauntlets protect the inside of the hand against cuts, but this typically is not the case

- Most historical gauntlets only armoured the back side of the hand with the inside of the hand only protected by a normal leather glove, so an unarmoured person with gloves would be no more likely to get cut by grabbing a sword blade

- Some historical techniques involving grabbing sword blades are, indeed, specialized for armoured combat, but many clearly aren’t

- My opinion? False.

- “The situations depicted are rare, outlier situations”

- My opinion? It depends on the time and treatise.

- While fencing treatises often show strange situations as a novelty, this is clearly not the case for many examples of blade grabbing techniques in many fencing treatises

- Many historical fencing treatises explicitly recommend using your hand to manipulate your own or your opponent’s sword

- Some treatises (especially later ones) do treat blade grabs as a curiosity rather than a core part of the fencing system they present

- It is fair to say that grabbing swords is never portrayed as the main way to defend against sword strikes and all authors show a preference for grabbing blunt portions of the opponent’s weapon when that’s an option

- My opinion? It depends on the time and treatise.

In my opinion, these techniques appear so often because they happened and people thought they were useful. We cannot simply dismiss blade grabs as stupid. So, assuming these people knew what they were talking about, how do these authors use blade grabs and how can they work?

How do swords cut?

You probably have a well-informed intuition about how sharp things cut, but let’s translate that intuition into words for sake of the discussion.

A blade can cut in two ways:

- Sufficient force is directed into the target through the edge of the blade

- The edge is pressed against the target while being dragged across it

If neither of those conditions are met, it doesn’t matter how sharp a blade is – it won’t cut. The sharper a blade is (or the weaker the medium being cut) the less force is required, but some force is always required.

In other words, a cut needs to have a certain amount of quality in order to actually do damage.

How can you grab a sharp blade “safely”?

“Safely” is a relative term here. Don’t get it twisted: grabbing a sharp blade is risky. There is always the possibility that something will go wrong and you’ll get cut. That said, fighting with sharp swords is also risky, and not just for your hands!

With that disclaimer out of the way, you can reduce the risk of being cut by compromising those two conditions under which a blade cuts:

- Reduce the amount of force directed into the target through the edge of the blade

- Reduce the chance of the blade sliding by immobilizing it

With these two approaches in mind, here are some mitigating factors that make a blade grab more likely to be successful. No one of these factors guarantees you won’t get cut, but the more of these apply, the less likely you will be injured:

- The blade is stationary

- This compromises cutting requisite 1; if it isn’t moving, that’s one less source of force

- Obviously, even a stationary blade can cut if you bring the force to it: if you punch a stationary sharp edge, for example, you’re gonna have a bad time

- You hold the blade mostly by pressing against the flats, not the edges

- This compromises cutting requisite 1; if the edge isn’t in contact with you, no force can be directed into you through the edge

- This is often feasible when grabbing your own weapon

- It may not always be feasible when grabbing your opponent’s weapon

- Something is preventing your opponent from pressing the edge into you

- This compromises cutting requisite 1

- For example…

- You have their arms in a lock

- You have more leverage over their sword

- Their sword is in an awkward position

- Your sword is opposing their sword, so they are mostly pushing against your sword and not you

- The surface area of the edge contacting your body is large relative to the forces being applied

- This compromises cutting requisite 1: the greater the surface area, the greater the force needed to achieve the same cut

- This is why you can lightly pinch a razor blade even with the edges against your fingertips

- You have a firm grip on the blade, so that it cannot slip

- This compromises cutting requisite 2

- You are wearing gloves

- This compromises cutting requisites 1 and 2 by adding a layer of protection and providing a firmer grip

- The blade profile is conducive to grabbing

- Consider that a razor blade is thin by design to allow for a finer edge – however, a razor blade scaled up to the size of a sword would either be heavy or floppy

- Real swords must strike a compromise between various attributes (such as blade width, stiffness, length, and weight) and some swords are “safer” to grab than others while remaining very good at cutting

“Don’t try this at home” Video Evidence

If you’re not convinced, you can find a lot of videos of people grabbing a sword with bare hands without getting cut. Here are a few:

- Robinswords: “Sword Grabs and Risk” (0:42)

- Skallagrim: “Why grabbing a sharp blade in a sword fight is not crazy” (8:57)

- Hand parries with a sharp rapier (4:25)

- Schola Gladiatoria: “The TRUTH about GRABBING sword BLADES” (18:16)

- Schola Gladiatoria: Samurai katana halfsword techniques: Gripping (~1:00)

What kinds of blade grabs do we see in historical sources?

Historical techniques describing manipulating your own or your opponent’s blade with your hands fall into a few broad categories. Some of these categories are more “controversial” in the modern HEMA scene than others.

- Grabbing your own sword blade

- What’s the motivation?

- To use your sword like a lever to facilitate grapples and throws

- To allow you make an extra strong parry

- To gain more dexterity with the point to facilitate thrusts through small gaps in armour

- To use your sword like a hammer

- To shorten the sword to use it like a dagger in very close quarters

- When is it safe?

- As long as you have control over your weapon, you can be reasonably certain what forces will act upon it and accommodate them

- How controversial among modern HEMA practitioners?

- Not controversial

- Is it allowed at modern tournaments?

- Almost always yes

- What’s the motivation?

- Grabbing your opponent’s blade after a solid cover

- What’s the motivation?

- A grab gives you a short window of relative safety to end the fight

- When is it safe?

- If your cover robbed the opponent’s weapon of its momentum, you have reduced the ways it can damage you

- If you oppose their weapon with yours, you can continue to control their weapon while grabbing

- If you have control over your opponent’s weapon arm through a grapple, their ability to move their weapon is limited

- How controversial among modern HEMA practitioners?

- Controversial

- Is it allowed at modern tournaments?

- Depends on the tournament

- Even if permitted, judges might have a hard time knowing if the grab would have been safe or not

- What’s the motivation?

- Deflecting a thrust with your hand (especially against thrust-centric weapons)

- This isn’t really a grab, but it is similar

- What’s the motivation?

- If your primary weapon is not occupied in your defense, you can attack with it while defending with your hand

- When is it safe?

- When thrusting, force is directed towards the tip, not the edge, so the main danger from the edge comes from it sliding across a cuttable surface

- These deflections are usually gentle sweeps, so, even if the opponent jerks the sword back, it will not have much or any contact with the hand

- Long, thrust-centric weapons often have less cutting capacity to begin with

- By contrast, we don’t see hand parries against the blades of short weapons like daggers and knives since they are fast and there is little blade to target (but because the weapon is short, you can often grab or deflect the arm instead)

- How controversial among modern HEMA practitioners?

- For swords without a cutting edge, not controversial

- For more cut-centric swords, somewhat controversial

- For short weapons like daggers and knives, the consensus is you should block their arms, not the blade, with your hands

- Is it allowed at modern tournaments?

- Depends on the tournament

- Even if permitted, judges might have a hard time knowing if the deflection would have been safe or not

- Hand parries as supplements to normal parries (especially against thrust-centric weapons)

- Again, this isn’t really a grab, but it is similar

- What’s the motivation?

- If your parry isn’t quite right, getting an incidental cut on the hand is better than getting stabbed in the body

- When is it safe?

- Since this kind of hand parry is only a backup to the normal parry, ideally your hand does not touch the opponent’s weapon at all

- How controversial among modern HEMA practitioners?

- Not at all controversial

- Is it allowed at modern tournaments?

- Yes, but – if your arm does get hit with quality – your opponent still gets points

- If you block a hit to a high-value target with your arm, some tournaments award your opponent the points for the high-value target to discourage sacrificing limbs for points

If you look through the images at the beginning of this post, you can sort the blade/hand interactions shown into these four categories.

What kind of blade grabs do we NOT see in historical sources?

By contrast, here are some types of blade grabs that no one seems to recommend:

- Grabbing or deflecting your opponent’s blade with your hand as your primary method of defence

- Grabbing or deflecting the blade of a small weapon like a knife or dagger with your bare hand

- Intentionally grabbing a moving blade without first arresting its momentum with a normal parry

- Deflecting a cut with your bare hand

- “But what if I just whack the flat of the blade with my hand?” Nope, still won’t work – check out Sword STEM’s article here

- Catching your opponent’s cut with your bare hands

- This only works in anime

Please, never try this

Leave a comment