Introduction

Fiore’s art of arms is not easy to summarize because it is not presented as an outline of principles or a how-to manual, but as a set of illustrative examples. This is consistent with the scholastic method of teaching that was common in the middle ages. This a form of inductive pedagogy, where the student intuits principles from exposure to many examples. Contemporary pedagogy is usually more deductive, so most modern readers expect an instructive text to outline principles and give explicit instructions.

An additional challenge is the general lack of explicit technical and tactical advice. Fiore often gives explicit instructions, but he also leaves a lot unsaid. Often, it isn’t clear how a situation emerged and what the salient features of the situation are. For example, both the masters of wide play with the longsword are shown with the left foot forward and in a mandritto crossing – is it important that the left foot be forward in a mandritto crossing in largo? Fiore doesn’t say. We can only look at the plays and surmise whether it is.

My goal with this post is to trim down what is a large and rich text into as concise an outline as possible. Information will necessarily go missing in this process, but I hope that the reorganization and interpretation of Fiore’s text will make it easier for a person unfamiliar with Fiore to get a well-informed overview quickly. I have focused on the longsword because that’s what I mostly train, but – as anyone will tell you – Fiore presents a system where the different sections are intended to supplement each other. As such, I’ve incorporated insights from other sections of the text as appropriate.

Who is Fiore?

Fiore Furlano de’i Liberi de Cividale d’Austria was a fencing master born to a knightly family in Cividale del Friuli in what is now northeastern Italy.

Four manuscripts attributed to Fiore are known to survive:

- The Getty (ca. 1404)

- The Morgan (ca. 1400-1410)

- The Pisani-Dossi (10. February 1409)

- The Florius (ca. 1410s or 1420s)

In the Getty Manuscript, Fiore writes that he has studied the art of arms for at least forty years. From that, we can presume he was born sometime around 1350.

Most of what we know about Fiore comes from his fencing manuscripts. By his own account, Fiore was interested in fighting from a young age and learned the art of arms from many German and Italian masters “with much labor and expense”. He names several of his students, many of whom were condottieri (mercenary captains) active in northern Italy, some of whom were famous in their time.

“Flowers of Battle Volume 1” by Tom Leoni and Gregory Mele includes some additional biographical information about Fiore. He apparently lived for some time in the city of Udine. An entry from the records of the city dated 3 August 1383 states that a “Maestro Fiore de Cividale, dimicator” (“fencer”) was granted citizenship and the city council put him in charge of the city’s ballista crews and had him “inspect and repair all the weapons of the town’s armory,” specifically, “the large crossbows and other arrow-launching weapons”. Another document dated 1384 states that he was assigned to a military company as an explorator (a sort of reconnaissance role). The last mention of Fiore outside of his own works is a document from 1384 which states he was appointed to serve in a law enforcement role in the city of Gemona. (*Biographical info and quotations from historical documents taken from “Flowers of Battle Volume 1” by Tom Leoni and Gregory Mele, p. 34)

The Gloss

Color Code

- Black text: based on my own experience or opinions that I’ve heard

- Purple text: directly based on Fiore’s text

- Blue text: very much my opinion

Armizare

Armizare is Fiore’s word for his art, the “art of arms”.

If terminology is something you find interesting, you can find a glossary of terms from Armizare here.

Four virtues of Armizare

See here for a more detailed explanation.

These virtues apply to all aspects of fencing. You can use them to self diagnose what’s going well or poorly.

- The Lynx: Foresight

- The Lion: Courage

- The Elephant: Fortitude

- The Tiger: Speed

Masters and Students: Fiore’s Portrayal of his Art

See here for a more detailed explanation.

Fiore illustrates important concepts with characters who are either “masters,” “students,” or “players.”

- Masters of battle or first masters

- Depicted at the beginning of a section wearing a crown

- Demonstrate the postures that make up the fundamentals of the art of arms

- These postures are called Poste or Guardie

- Remedy masters or second masters

- Also wear a crown, but are depicted as engaged in combat

- Represent situations that arise from the postures

- Students

- Identified by a golden garter below the knee

- Represent actions that result from the position of their remedy master

- Counter-remedy masters or third masters

- Wear a crown and a garter

- Demonstrate techniques that counter the previous remedy master and his students

- Counter-counter-remedy masters or fourth masters

- Also wear a crown and a garter

- Demonstrate counters to a third master and his students

- Fiore writes that techniques rarely go beyond the third master “after which lies danger”.

- Players

- Figures with neither a crown nor a garter

- Represent the opponent

What kind of sword?

Contemporary historical fencing practitioners would refer to the sort of sword Fiore depicts as a longsword. Typically, a longsword…

- can be worn at the side

- can be used in one or two hands

- has a straight, double-edged blade that tapers to a narrow point

- has a simple crossbar for a guard

However, “longsword” is a modern term and historical swords that would fall into this category come in a huge variety.

What does Fiore have to say about swords?

- Fiore refers simply to “the sword in one hand” and “the sword in two hands”

- The illustrations suggest that the “sword in one hand” is the same kind of sword as the “sword in two hands” just held with one hand

- Fiore mentions that certain techniques work well with the one- or two-handed sword suggesting that the depicted sword doesn’t need to be the kind of sword used

- The irrelevance of the specifics is underscored by the theme of cross-weapon applicability in Fiore text. If your sword is particularly big and heavy, it might behave more like a poleaxe; if it’s really small, dagger plays will come up more

- There is a persistent myth that Fiore requires a shorter longsword than other sources, yet Fiore himself writes that certain guards are better with a longer sword and certain guards are better with a shorter sword, suggesting that Fiore doesn’t demand a specific length

- Given the diversity of medieval longswords, this shouldn’t come as a surprise

- Some actions will occur more frequently or be easier with a shorter or a longer sword, but this should not be understood as a prescription.

Parts of the sword

- Blade

- Point

- Long edge = true edge

- Short edge = false edge

- Weak

- Middle

- Strong

- Hilt

- Guard

- Handle

- Pommel

Holding the sword

- General principles

- Keep your wrists in line with your forearms avoid stressing your wrists

- Keep your elbows tucked in (form a triangle with your arms, not a circle)

- Grip tightly while striking or parrying, but otherwise relax your grip to reduce fatigue

- If you have trouble with a movement, try relaxing your grip and your posture first

- Fiore includes illustrations where the pommel is held by the non-dominant hand – it is historically accurate to do so – but most modern experimentation shows that holding the sword with the hands together is better for cutting

- Relaxed grip

- When the sword is not extended in front of you, or you are not actively fencing, hold the sword however is comfortable keeping the general principles above in mind

- Extended grip

- When striking with the sword, or holding it in front of you, grip it like this: How to Cut with a Longsword – In 15 Minutes

Stance and Footwork

- General principles

- Your posture and your steps should not hurt you

- Muscular stress is okay, joint stress is not okay

- No lateral force on your knees: point your knee in the same direction as the foot of the same leg

- If you physically cannot do something, either work towards improving your mobility/ability or – barring that – adapt the posture to something you can do

- Posture and footwork are goal-oriented and some goals are contradictory

- A posture optimized for stability will be sub-optimal for agility

- A posture optimized for agility will be sub-optimal for stability

- A decisive step is not the same as a cautious step, but both are sometimes necessary

- A good posture lets you easily and efficiently switch between goals

- This means there is no one “right way” to stand or step – however, if your posture does not facilitate your goals, it can still be “wrong”

- In one play, Fiore instructs the reader to take a “narrow stance” (without saying what that means) which implies that Fiore is aware that different stances exist and are sometimes appropriate

- An experienced fencer makes their steps intuitively, dependent on their goals, and seldom thinks in terms of names or choreographies

- Fiore shows stances that generally appear to have the weight more on one leg than the other – sometimes the front, sometimes the back

- The unweighted leg will be easier to move – keep this in mind and you’ll notice that how you distribute your weight influences which steps you’ll want to take

- Your posture and your steps should not hurt you

- Steps

- Increasing (accressere)

- A step with one foot that increases the distance between your feet in the x- and/or y-axis without changing the orientation of your feet (i.e. front and back foot remain the same)

- Decreasing (decressere)

- A step with one foot that decreases the distance between your feet in the x- and/or y-axis without changing the orientation of your feet (i. e. front and back foot remain the same)

- Passing (passare)

- Pass forward: The back foot steps such that it is now the front foot

- Pass backward: The front foot steps such that it is now the back foot

- Returning (tournare)

- Swapping which leg is forward by first withdrawing front foot and then the advancing the back foot

- Increasing (accressere)

- Turns of the body and sword

- Stable turn (volta stabile)

- When standing still, you can play in front and behind on the same side

- Interpretation: Any fencing action where which leg is forward remains the same

- One kind of stable turn involves pivoting in place

- Your head should not bob up and down as you pivot; the turn is a rotation in the x-y-plane, not affecting the z-axis

- The farther your feet are apart, the more such a pivot will result in shifting your weight from one leg to the other; you can use this fact to intentionally shift your weight

- When standing still, you can play in front and behind on the same side

- Half-turn (mezza volta)

- By passing forwards or backwards, you can play on the other side

- Interpretation: Any fencing action where the leg position changes due to a passing step forward or backward

- By passing forwards or backwards, you can play on the other side

- Full-turn (tutta volta)

- One foot remains in place and the other foot and the body with it turn around that leg

- Interpretation: Any fencing action where one leg circles around the other

- This does not need to be a 180° or 360° rotation; the important thing is one leg circling around the other

- One foot remains in place and the other foot and the body with it turn around that leg

- Stable turn (volta stabile)

- Typical combinations of steps and turns

- Fiore only mentions the four steps and three turns, but I like to think of these as the building blocks from which all movements are made.

- It is not important to memorize these unofficial names (I include the names only to facilitate communication); an experienced fencer makes their steps intuitively, dependent on their goals, and seldom thinks in terms of names or choreographies.

- “Fencing step”

- Increase by moving the front foot forward, decrease by moving the back foot forward. You have made a fencing step forward.

- Increase by moving the back foot backward, decrease by moving the front foot backward. You have made a fencing step backward.

- “Gathering step”

- Decrease by moving the back foot forward, increase by moving the front foot forward. You have made a gathering step forward.

- Decrease by moving the front foot backward, increase by moving the back foot backward. You have made a gathering step backward.

- “Passing step”

- Pass forwards or backwards with a half-turn (that is, your hips are oriented to the opposite side from which they began)

- “Triangle step with a pass”

- Pass forwards or backwards offline, then do a full-turn around the leg you stepped with to reorient yourself towards your target

- “Triangle step without a pass”

- Increase moving one foot offline, then do a full-turn around the same leg to reorient yourself towards your target

Fiore Introduces the Sword

Just before the first play of the sword in two hands, Fiore has the sword “introduce itself” to the reader.

“I am the sword and I am deadly against any weapon; the spear, the axe and the dagger are worthless against me. I can become extended or withdrawn; when I get near the opponent, I can enter into close play, perform disarms and grapples. My art is to perform breaks and binds; I am expert in covers and strikes, and I always strive to finish my covers with strikes. Come against me and feel the pain. I am royal, enforce justice, propagate goodness and destroy evil. Look at me as a cross, and I will bring you fame and a name in the art of arms.”

– Getty-MS, Introduction of the sword in two hands without armour

The description features plenty of the boastful grandstanding that is typical for Fiore, but it also fairly accurately and concisely summarizes how Fiore describes fighting with the sword.

- “I am the sword and I am deadly against any weapon” – The sword is a generalist, a tactically flexible weapon

- “I can become extended or withdrawn” – Postures either have the sword extended forwards or held close to the body

- “When I get near the opponent, I can enter into close play, perform disarms and grapples” – Fiore divides the plays of the sword into “wide” and “close”, as we will see later

- “My art is to perform breaks and binds; I am expert in covers and strikes, and I always strive to finish my covers with strikes” – Fiore discusses different covers (blocks, parries) with the sword; these could be divided into two categories: breaks and binds. Fiore typically portrays covers as a precursor to strikes.

- “Look at me as a cross, and I will bring you fame and a name in the art of arms” – Aside from the clear religious connotation, Fiore analyzes fighting with the sword by examining different crossings. The cross (=crossing) is, in his mind, of central importance to understanding fencing.

Attacking: The “Seven Strikes of the Sword“

Fiore describes four kinds of strikes:

- Cuts from above

- Cuts from below

- Cuts from the side

- Thrusts

Considering that cuts can be made as a forehand or backhand blow, we arrive at his “seven strikes of the sword”:

- Mandritto fendente (forehand descending cut)

- Fiore describes the trajectory of the fendenti by saying that they “split the teeth and travel down to the knee for good measure” – this is probably a mnemonic since fendere is “to split” and denti is “teeth” in Italian

- Riverso fendente (backhand descending cut)

- Mandritto sottano (forehand ascending cut)

- Fiore says that cuts from below, the sottani, either return down the same path with a fendente or “remain in posta longa“ – try making a cut from below that “remains in posta longa” and you’ll notice that it’s easiest when you make the cut with the false edge

- Riverso sottano (backhand ascending cut)

- Mandritto mezzano (forehand cut lying between fendente and sottano)

- Fiore writes that the forehand mezzani are made with the true edge of the sword

- Riverso mezzano (backhand cut lying between fendente and sottano)

- Fiore writes that the backhand mezzani are made with the false edge of the sword

- Punte (thrusts)

- Fiore writes that there are five kinds of thrusts – two from above on both sides, two from below on both sides, and one down the middle – but he probably thought “the eleven strikes of the sword” wouldn’t sound as good

Theoretically, all cuts can be made with either the true or false edge, but Fiore doesn’t discuss variations of cuts beyond what I’ve written above.

Poste: Guards

In my opinion, guards are useful for these four reasons:

- Getting a feeling for what positions the author thinks are most important

- Getting a feeling for the tactical preferences an author has for certain positions

- Getting a feeling for how the author thinks you should move

- Being able to talk about fencing (guard names being a mutually understood shorthand for positions)

Once you’ve learned how to move and fence, none of these are important during the bout (although you might consider point (2) during your fencing). Memorizing guards is not a productive way of getting better at fencing.

Fiore features guards prominently in his text and seems to use them for all four of these purposes.

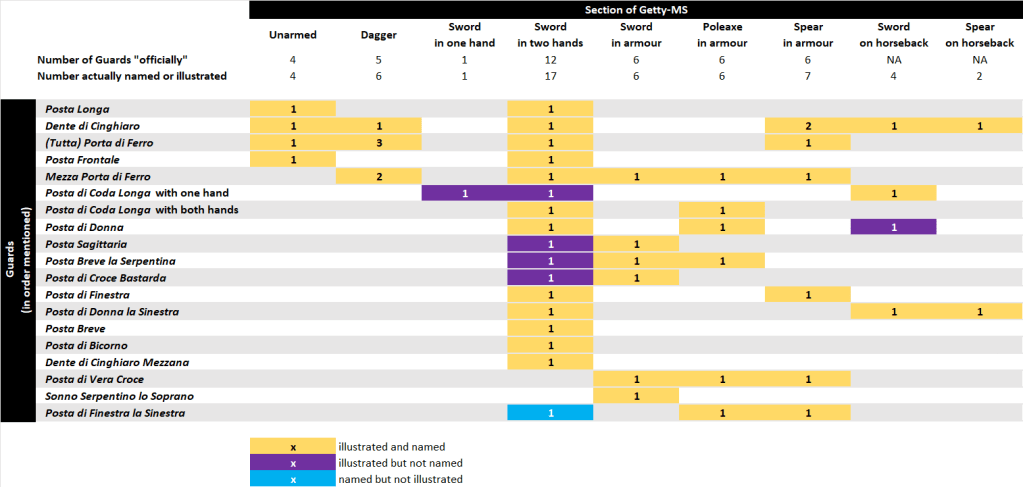

At the beginning of each section, Fiore illustrates a number of “first masters of battle” who demonstrate guards. The Getty-MS includes a lot of guards (by my count, 19 in total):

This graphic is provided mostly as a curiosity; I don’t think it is important to memorize the information in the table. To understand the role of guards in Fiore’s art, more observations are necessary:

- Some of the guards are repeatedly introduced in different sections

- Some guards are introduced without being named and only given a name in later sections

- Some guards are referenced in the text of certain sections without a corresponding “master of battle” demonstrating the guard at the start of the section

- Some guards that have the same name don’t look exactly the same; there is variation within each guard

- There seems to be some sort of intentionality behind the numbers, perhaps symbolic

- Fiore says there are 5 guards of the dagger and then, at the end of the dagger section, introduces a 6th guard with the dagger

- Fiore says there are 12 guards of the sword in two hands without armor, but he names more than 12 such guards

- Dente di Cinghiaro Mezzana seems strange to include, since it appears to do nothing differently from Dente di Cinghiaro – in other versions of the manuscript, Fiore replaces this guard with a different one (either an alternative Posta di Donna or Posta di Finestra la Sinestra depending on the manuscript); he seems to have just really wanted 12 guards

- Fiore names certain guards of the sword that he says are “better in armour” but then only shows some of those guards in the “sword in armour” section

- Many guards are illustrated in techniques, but Fiore does not explicitly say “this is xyz guard” (for example, posta longa is only mentioned in two sections, but it appears every time someone has their arms stretched out)

- Many positions are illustrated that cannot be definitively classified as a guard

- Fiore writes that every guard can make a stable turn and a half-turn – this possibly means every guard may be front- or back-weighted and every guard could have either the right or the left leg forward

My key takeaways from all of these observations:

- The guards listed at the start of each section are, perhaps, the “main” guards for that section, but you can and should apply the principles from other sections to any weapon type

- The guards Fiore presents are not a comprehensive list of all positions one passes through while fencing, but maybe important “touchstones” or waypoints

- We can presume that the guards Fiore specifically illustrates are highlighted for good reason

I have a handout with a German translation of the 12 guards of the longsword here.

Movement

For a beginner, I recommend using the guards as a starting point for understanding how to move; simply standing in a picture-perfect guard is not very useful.

- Try moving between various positions exactly as they are illustrated. What steps and turns are necessary to do so? Take your time and experiment.

- Take up any guard. Pivot in place. What changed?

- Take up any guard. Pass forwards or backwards. What changed?

- How do your answers to (2) and (3) change if you keep the orientation of your upper body the same during the turn? If you change the orientation of your upper body with the turn?

Tactical preferences

Fiore seems to classify guards of the sword without armour by the following attributes:

- Pulsativa (striking), stabile (stable), instabile (instable)

- He does not define these terms

- Extended (hands in front of the body) or withdrawn (hands retracted)

- Sword on the right side, left side, or in the middle

- Sword held high, low, or in the middle

There is some good general tactical advice in the guards section:

- Guards that look similar are good counters to each other because they can do similar things

- If a guard is extended (sword held in front of the body), the most extended guard (or the person with the longest sword) will hit the other person first

- Striking guards are good at striking!

- Instabile / point-forward guards are more reliant on probing and deception

- Stabile / withdrawn guards are good for waiting provided you have time to react to your opponent

The most important observation from Fiore’s comments, in my opinion:

- All guards with the sword on the dominant side (right side for right-handers) can exchange and break points

- All guards with the sword on the non-dominant side (left side for right-handers) can break points, but do not mention the exchange of points

This is because it is easier to thrust with opposition from the dominant side and easier to break from the non-dominant side. This observation is echoed later in the spear section where Fiore writes:

“Any offline guard with the short lance or a short sword is enough to wait for any long handheld weapon. Right-sided guards will cover and, while covering, pass and strike with a thrust. Left-sided guards will cover with a beat aside, and strike with a cut – but are not as good at riposting with a thrust.”

– Getty-MS, Description of Mezza Porta di Ferro with the spear

Covering with opposition from the dominant side and covering with a beat from the non-dominant side are – in my opinion – the first two defensive techniques a beginner should learn.

Defending: Two Archetypes

A glib interpretation of Fiore is that he only has two defensive techniques for wide play:

- The exchange of points (scambiar di punta)

- The breaking of the point (rompere di punta)

and everything else is just a variation of those two. There is some merit to this idea. Even though these two defenses are described as defences against thrusts (or, literally, as defences against points), a cut at full extension passes through the same position as a thrust.

The covers Fiore describes fall into two broad categories:

- Opposing the opponent’s blade with your own

- From there, we can:

- Keep the point on the opponent and stab them while maintaining opposition (the scambiar di punta is a special case of this)

- Let the opponent’s blade harmlessly slide off to the side then hit them however we wish

- Use the cover to enter into close play

- From there, we can:

- Beating the opponent’s blade out of the way (the rompere di punta is a special case of this)

- From there, we can:

- Hit them if they’re open

- Cover their blade and enter into close play

- From there, we can:

Of course, this list of options isn’t exhaustive. You could also simply retreat after a cover, for example. But remember from the sword’s introduction: “I am expert in covers and strikes, and I always strive to finish my covers with strikes”.

As mentioned in the previous section, (1) is easiest from your mandritto side and (2) is easiest from your riverso side.

A Note on Grappling at the Sword

- All the grabs and grapples at the sword that Fiore illustrates show the grapple being done with the non-dominant hand, with your dominant hand remaining holding your own sword (unless you drop your own sword entirely)

- It is possible, and sometimes convenient, to let go with your dominant hand and hold the sword near the pommel with your non-dominant hand while going for a grapple, but I recommend against the learner doing so

- If you keep your dominant hand on the sword while grappling, then the logic of when to use the grapples Fiore shows will be more apparent

- Keeping your dominant hand in place also has the obvious advantage that you can use the sword to cover and strike better

Zogho Largo: Wide Play

In the Getty-MS, Fiore illustrates 20 plays of the sword in two hands without armour in wide play.

- First remedy master crossed at the points of the swords + 1 student

- Second remedy master crossed at the middle of the sword + 16 students

- Counter remedy master showing the counter to the punta falsa

Fiore does not define largo (which literally means “wide” or “loose”). The techniques in this section are focused on bladework. Fiore shows some grapples in the largo section, but they are either longer-ranged grapples (like a kick to the knee or a blade grab) or follow-ups to longer-ranged techniques. So, while measure is certainly relevant to whether or not a situation is largo, measure is apparently not the whole story.

What is largo?

- You are in range to strike with at most a passing step

- If there is a crossing, it is safe to leave it

- The surest path to safety is behind you; it is possible to retreat safely

- Guy Windsor defines zogho largo as a situation in which you are free to strike because the opponent’s point is not in presence (lengthy discussion here) – I think that’s also a good way of thinking about it and it overlaps a lot with retreat being possible

How do you “largo“?

I summarize the situations covered in this section as follows:

- Widest measure

- Direct line is opening: stab them in the face

- Direct line is closing: cut to the other side

- Middle measure

- Center won: stab them or cut them without changing sides while moving out of the way

- Center contested: grab their blade then hit them

- Center lost: cut to the other side remaining covered while moving out of the way

- Middle measure, special situations

- If they attack your leg, pull it back and hit them in the head as you do

- If the situation is ambiguous, you can kick them in the testicles

- If they rush you or try to parry while you have their blade grabbed, you can break their leg with a kick

- Both the exchange of points and breaking the point are specific variations of “middle measure: center won” above

- The Punta falsa

- I think this is just an example of how to get to half-swording from wide measure

- It may also be teaching the principle of feinting, but it’s certainly not the best feint nor the most obvious

- Fiore writes that this play is “better in armour”

- He writes this in several places throughout the text and I think this is code for “this play is kinda risky”

Although footwork is hugely contextual, a general rule of thumb is that Fiore shows movement towards where you are “winning” (and, conversely, away from where you are “losing”).

- So, if you have won the center with good opposition (as in the exchange of points), you move into the bind.

- If you have lost the center (as in the culpo di villano), you move away from the side your opponent is dominating (where you are “losing”) and towards the side that is opening up (where you are “winning”).

- The same applies if the reason you are “losing” the side is because you willingly forfeit the position

- If you leave the bind to strike, you have “abandoned” the center and are thus losing there, so strike while moving away from the bind (taking a step backwards, out to the side, or forward and at an angle away from the bind depending on the situation).

I have a handout summarizing the wide plays here.

Zogho Stretto: Constrained Play

In the Getty-MS, Fiore illustrates 23 plays of the sword in two hands without armour in close play.

Fiore does not define stretto (which literally means “narrow” or “constrained”), but it is clearly a situation where grapples happen.

What is stretto?

- You are in a crossing and it is not safe to leave it

- The surest path to safety lies in front of you

- This strongly implies there is pressure in the crossing

- You are physically close enough to enter into a grapple and it is safer to do so than the alternative

- Guy Windsor defines zogho stretto as a situation in which you are not free to strike because the opponent’s point is in presence (lengthy discussion here) – I think that’s also a good way of thinking about it and it overlaps a lot with retreat not being safe

How do you “stretto“?

I like to categorize the plays like this:

- Pommel strikes

- Grabs

- Wraps

- Throws

- Disarms

Practically, throws and disarms only happen after you’ve already had the opportunity for a grab, wrap, or pommel strike, so I like to consider grabs, wraps, and pommel strikes as your entry into stretto and the remainder as follow-ups.

I like to think of entries like this:

- As you are entering, is bind on your mandritto or riverso side?

- The bind is on my mandritto side: Remain in the bind, and hit them in the face with your pommel (optionally controlling their weapon arm with your non-dominant hand at the same time) then strike or throw them

- The bind is on my riverso side: Remain in the bind, and use your non-dominant hand to control your opponent’s weapon or weapon arm (such as with a wrap) then strike them

(1) most commonly occurs from a mandritto crossing and (2) most commonly occurs from a riverso crossing or the cover of the sword in one hand section.

I have a handout showing the most common stretto-techniques here.

When do you “stretto“?

Critically, stretto techniques require a stretto-situation. If your opponent is free to retreat while you are entering, they can do so and hit you while you are entering.

When is your opponent is not free to retreat?

- When they are stepping forward – they can’t step backward if they are in the middle of a step forward

- When their stepping backward frees you to strike them – in which case, they either don’t retreat (permitting your stretto-technique) or they do retreat and you hit them

- When you are sufficiently close that their stepping backward doesn’t free them to strike – in which case they can try to escape but will simply fail

There’s a stereotype that Fiore is all about entering into grappling. Some people go so far as to claim that Fiore is always looking to wrestle. I have a more nuanced view. At the beginning of the stretto section, where the stretto crossing is presented, Fiore writes:

“We have crossed our swords: this is the crossing from which we can make all the plays that follow. Both of us could perform each of them.”

– Getty-MS, 1st master of zogho stretto

As we enter stretto, our opponent is just as capable of using stretto techniques as we are. If we haven’t set up the situation in our favor, we are giving our opponent a chance to counter us. So, I think Fiore would say it is not wise to enter stretto without a certain amount of foresight.

In the introduction of the Getty, Fiore writes:

“When you engage in wrestling, you must assess whether your opponent is stronger or bigger than you, and whether he is much younger or older. You also need to take note of whether he places himself in any of the guards of wrestling. Be sure to pay attention to all these things. And whether you are stronger or weaker, use the grapples that arise from the binds and be sure to know how to defend against those which the opponent uses against you.”

– Getty-MS, introduction

In this and other places in the text, Fiore talks about seeking grapples when you see that you have an advantage. Fiore tells us in his description of the guard for the sword in two hands that Dente di Cinghiaro is good at defending against stretto, suggesting that it is sometimes appropriate for a fighter to avoid close play. This seems like a more reasonable and nuanced view of wrestling to me.

A Compact Armizare Toolbox

As mentioned in the introduction, we modern people love explicit instructions (and lists!). Synthesizing the plays of the sword, both the largo and stretto sections, I would distill Fiore’s instructions into these 10 “rules”:

- No Crossing / Out of measure

- Fiore offers some general advice in the guards section for how to approach starting the fight

- Largo

- Attack into the opening line (not the open line, the opening line)

- If they attack, bind (easiest from the mandritto side) or break (easiest from the riverso side) their attack and strike

- If their blade isn’t moving in a way that can hurt you and you can reach it, grab it with your off-hand then strike them

- If they attack and overwhelm your parry, let their sword slide off while stepping out of the way, then hit them

- If they attack your legs, pull your front leg back and hit them in the head

- Don’t forget that you can use your legs to attack as well

- Stretto

- If you can push their dominant elbow with your non-dominant hand, do so

- If they push your blade to your outside, hit them in the face with your pommel

- If they push your blade to your inside, wrap them

- Be prepared to follow up these grapples with weapon strikes, counter grapples, and throws

I think every play of the sword in one or two hands is just a variation, a continuation, or a special case of these “rules”.

I have a beginner’s guide handout summarizing this short form toolbox with more fencing-specific details here.

What I like about Fiore’s System

If Fiore’s fencing system were a machine, it would…

- …have relatively few moving parts,

- …have generous manufacturing tolerances,

- …be able to do a variety of jobs pretty well without modification,

- …be fairly intuitive to use, and

- …have a long and convoluted user manual with lots of cross-references and without a table of contents 🙂

To keep the machine metaphor going, Fiore’s fencing system isn’t a sportscar, it’s a jeep. If you want to, you can use your interpretive freedom to dress it up into a “luxury” jeep that a white-collar commuter in the suburbs might drive, or you can strip it down to the sort of thing that would be at home trundling across rough terrain in a warzone.

Fiore achieves this by:

- Emphasizing gross motor movements

- All attacks and defences are gross motor movements

- All grapples are gross motor movements

- All steps are gross motor movements

- No dynamic grip changes during an action

- It should all work in armour or without, so exceptional range of motion and fine finger dexterity aren’t necessary

- Emphasizing movement patterns with broad applications

- No attacks or defenses that only work under very specific circumstances

- All parries are essentially the same: the same bind from the mandritto side or break from the riverso side can cover almost all angles of attack

- No complex sequences of attacks or defenses to memorize

- Movement patterns are often the same across weapon types

- Often the same motion works whether you have a dagger, a sword, a pole axe, a spear, or a stick

- Wrestling techniques that work against unarmed or armed opponents

- No techniques that won’t work in armour

- The end of one technique is the beginning of another – link them together until the fight is done!

- You’re on guard, but -surprise!- there’s an opponent sneaking up from behind you! Do a stable turn and now you’re facing him and already in a guard you know.

- No attacks or defenses that only work under very specific circumstances

- Keeping mental load down by…

- presenting some tactical templates in the guards section

- despite naming way too many guards, similarities across them become clear over time:

- left-sided guards all act more or less the same

- right-sided guards all act more or less the same

- instable guards all act more or less the same

- despite naming way too many guards, similarities across them become clear over time:

- emphasizing binary decisions

- Go or no go?

- Largo or stretto?

- Parrying from the right or the left? You have one motion + follow-ups for each

- Entering on the right or the left? You have one motion + follow-ups for each

- presenting some tactical templates in the guards section

- Not sweating the details

- This can be frustrating, but it can also be freeing

- Fiore does not make sweeping prescriptions about how you must do this or that

- I often get the impression that Fiore is intentionally ambiguous because he knows a one-size-fits-all answer would be wrong

Leave a comment