Who is Fabris?

Salvator Fabris was an Italian fencing master who lived from 1544-1618. He wrote a fencing treatise called De lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme (“On Defense, or the Science of Arms”). It was written in the 1590s, published in 1606, and is regarded as one of the most influential fencing treatises of all time.

My Notes

These are my notes on that treatise. My goal is to provide a concise outline of the fundamentals of the sword alone as Fabris describes them. This is simply a summary of Fabris’s writing; I have done my best to avoid any interpretation of my own, but where I cannot avoid commenting, I have written my own opinion in blue.

I used three sources for this summary:

- A. F. Johnson’s English translation available for free on Wiktenauer

- Tom Leoni’s English translation available here

- Tom Leoni’s English translation of the Vienna Anonymous fencing treatise available here

- This is a 17th century gloss of Fabris and Capoferro that provides additional insights into the works of both masters

For now, I have limited the scope of this summary to only the fundamentals of the sword alone. This summary does not include:

- The plays of the sword alone from book 1

- The fundamentals of sword and dagger from book 1

- The entire contents of book 2

Perhaps I’ll expand it in the future.

Book 1

- Chapter 1: The principles of the sword alone

- From knowledge of the sword alone, one can derive the principles that apply to all other weapons

- There are only four guards and, although these can take many forms, all fencing positions fall into one of these four categories

- Later chapters will discuss how to approach the opponent most securely, but ultimately it doesn’t matter how you approach as long as you understand…

- distance,

- strong and weak positions, and

- exposed and unexposed parts

- There are two distances, wide (misura larga) and narrow (misura stretta), and what is appropriate at one distance is not necessarily appropriate in the other

- Roadmap for the chapters ahead:

- Description of the four principle guards

- Divisions of the sword

- Counterpositions

- Distances

- Other things

- Chapter 2: Description of the four principal guards and the origin of their names

- First (Prime)

- Palm of the weapon hand facing outward

- knuckles inward

- Second (Seconde)

- Palm of the weapon hand is horizontal facing down to the ground

- Knuckles pointing up

- Third (Tierce)

- Palm of the weapon hand facing inside

- Knuckles pointing outward

- Like you are offering someone a handshake

- Fourth (Quarte)

- Palm of the weapon hand facing upwards

- Knuckles pointing down to the ground

- Generally, especially with the sword alone, these guards should be formed with the point directed forward

- Strictly speaking, there are more than four possible positions because the hand can be placed in an intermediate position between these four, but for simplicity’s sake we only refer to these four

- Specifics will be discussed later

- First (Prime)

- Chapter 3: Divisions of the sword: the weak and the strong

- There are four parts of the sword:

- The first quarter of the blade nearest the hand is strongest for parrying

- The second quarter extends from the first to the middle of the blade and is still good for parrying, albeit somewhat weaker

- The third quarter extends from the middle toward the point and is bad for parrying (especially against cuts)

- The fourth quarter should not be used for parrying at all but is best for wounding

- Cuts are most effective around the transition between the third and fourth parts

- a cut with the third part of the blade is half as effective as a cut near this transition

- These four parts can be simplified to just two:

- The first and second are the strong (forte), used for defense

- The third and fourth are the weak (debole), used for offense

- There are four parts of the sword:

- Chapter 4: Method of forming the counter-positions

- Definition of a counter-position

- You are not touching your opponent’s sword with your own

- Your body, arms and sword are positioned such that your opponent’s weapon point cannot travel in a straight line and hit you in the body

- Your sword is positioned in a stronger position relative to the opponent’s sword

- The advantage of a counter-position

- If your opponent attacks directly, you will not get hit

- Therefore, opponent must move their sword elsewhere to attack you directly, which will increase the duration of his action so that there is plenty of time to parry

- What if your opponent changes positions in response to your counter-position?

- If your opponent changes position on your advance, you must be prepared to…

- Immediately attack if this change is done at narrow range

- Immediately take up another position of advantage if not

- If your opponent changes positions while retreating, you cannot hit them, so form a new counter-position and proceed anew

- If your opponent changes position on your advance, you must be prepared to…

- Additional rules for changing counter-positions

- If your opponent is in range to hit you with only a small step of the front foot, you must change counter-position without stepping so that you can parry or retreat if he attacks during your position change

- Place the sword into a position of advantage slowly so that you can abandon your movement if the opponent attacks during it

- Summary

- To approach the opponent safely…

- Form a counter-position

- Approach cautiously as described above

- If your opponent reacts in a way that disconcerts you, it is better to break off and seek advantage anew than to continue

- To approach the opponent safely…

- Definition of a counter-position

- Chapter 5: Explanation of the two distances, wide and close, and how to acquire the one or the other with least danger

- Definition of wide distance (misura larga)

- You are in wide distance when you could hit by advancing the rear foot to the front (or by widening your stance with a step forward with the front foot)

- Definition of narrow distance (misura stretta)

- You are in narrow distance if you can hit without moving your feet by merely outstretching the arm and leaning with the body

- In narrow range, if your opponent does not move, you can hit them in one Tempo even if they are in a counter-position!

- How to enter wide distance

- Form a counter-position a little out of distance

- Carefully enter into wide distance, being prepared for the possibility that your opponent will advance too and attack as you enter

- As you enter wide distance, that is a good moment to feint or otherwise provoke your opponent

- How to approach in wide distance

- If you are already in wide measure…

- If your opponent takes a step forward, you can hit him on the nearest exposed part even if he has not moved his weapons

- If your opponent moves his weapons, but not his feet, he will have enough time to parry an attack, so you should either…

- ….proceed to narrow distance instead

- …perform an indirect attack if you have the time and space to do so

- If your opponent retreats, you proceed cautiously anew

- If you are already in wide measure…

- You cannot move your foot in less than two Tempi

- A step with one foot has two parts: lifting it and placing it down.

- Even though lifting the foot results in each step being two tempi, it is a better habit to lift the foot than to push it along the ground

- “For this reason some push the foot forward by scraping it along the ground, which is well enough in the hall, but in the street is likely to lead to a fall because of the many unevennesses. It is better then to lift it to make sure of not stumbling.”

- How to enter narrow distance

- If you are in wide distance and wish to advance to narrow distance, you must advance cautiously because your opponent can attack and retreat on your advance

- Form a counter-position

- Put all of your weight on your back foot as you lift your front foot

- If your opponent attacks into this movement, you can parry and riposte while placing the foot down

- If the opponent does not act as you raise your foot, place your front foot forwards keeping all your weight on your back leg and your body still in wide distance

- If your opponent still hasn’t moved once your foot is on the ground, you can now hit without stepping – that is, you are in narrow distance!

- If your opponent retreats as you place your foot, you are still in wide distance and should shift your weight forward and bring your back leg forward to a comfortable fencing stance

- If you are in wide distance and wish to advance to narrow distance, you must advance cautiously because your opponent can attack and retreat on your advance

- How to approach in narrow distance

- In narrow distance, do not advance the body at the same time as the foot; the front foot advances first with the body staying behind

- How to retreat after hitting

- Your retreats in narrow distance do not need to be as cautious as advances

- After hitting, just get out of there as far as you can

- How to deal with a retreating opponent

- Do not chase a feeling opponent, but proceed with additional caution

- “for many feign a retirement with the object of drawing on their adversary and seeking an opportunity to hit in the moment of his pursuing”

- “It is better not to pursue one who flees, but rather to feign reluctance in order to reassure him and so draw him on, and then to seize an opportunity which he will not have time to avoid”

- Do not chase a feeling opponent, but proceed with additional caution

- Definition of wide distance (misura larga)

- Chapter 6: Discourse on rushing in with the sword extended and the principles of the two times, showing that it is better to control the sword and observe the correct time

- There is no good reason to hurl your arm violently to give a thrust greater force

- If your opponent correctly defends the line you are attacking, you cannot change lines because of the violence of your motion

- If your opponent can deflect your attack in the same direction as the momentum you have given your attack, then it is even easier for them to parry – so easy, that even their debole is stronger than your forte

- Adding momentum to a thrust often throws off its accuracy

- Adding momentum to a thrust often brings your own weapon out of line

- It is more difficult to perform a subsequent attack after failing to hit with a violent thrust

- Violent thrusts are so slow that a two Tempo parry and riposte is often sufficient to defend and wound (which otherwise wouldn’t be the case)

- If you try to feint with a violent thrust, the feint is so slow and obvious that it is relatively easy for your opponent to wound you while doing so

- One-tempo defenses are generally better than two-tempo defenses

- If you hit your opponent as he advances, he will not have time to recover

- If your attack occurs after your opponent has already recovered from their attack, you open yourself to the possibility that they will parry and attack again

- However, with the sword alone great judgement is required to defend and offend at the same time

- Why the two-tempo Beat+Riposte is inferior to parrying and hitting at the same time

- Beating the opponent’s attack away and then striking would work fine if there were no possibility of your opponent deceiving you, but there are many ways your opponent can deceive your beat

- A beat necessarily brings your own weapon out of line

- A beat necessarily frees your opponent’s sword

- If you attempt to beat your opponent’s debole, it sometimes happens that (through skill on your opponent’s part or luck) you beat against your opponent’s forte and the beat fails

- If you successfully beat your opponent’s debole, but your opponent is proceeding carefully in control of their weapon, you have displaced their debole, but not their forte, so they are still able to parry your riposte in time

- What you should do instead:

- If your opponent cannot free his sword, he cannot hit you; a sword in subjection is harmless

- Therefore, you should engage your opponent’s debole and hold your opponent’s sword in subjection

- As your opponent attempts to avoid subjection, you adapt

- either hit while covered, or

- subject your opponent’s sword anew

- Keep up the pressure on your opponent, keeping your point on him without withdrawing your sword proceeding steadily to the body with the point

- Hit as the opportunity presents itself

- This approach cannot be done by someone who thrusts with violence or rushes in

- There is no good reason to hurl your arm violently to give a thrust greater force

- Chapter 7: Discourse on cutting

- The four cuts

- Mandritto

- Cut from the dominant side

- (From right to left for a right-hander)

- Riverso

- Cut from the non-dominant side

- (From left to right for a right-hander)

- Sottomano

- An upward vertical cut originating from the dominant side

- Montante

- An upward vertical cut originating from the non-dominant side

- Fabris writes that there are four cuts, but his cutting diagram shown later in chapter 18 is more specific and includes more than four kinds of cuts including:

- Fendente: almost vertical cut from above

- Squalembrato: downward diagonal cut

- Tondo: horizontal cut

- Falso dritto: upward diagonal cut with the false edge originating from the dominant side

- Falso manco: upward diagonal cut with the false edge originating from the non-dominant side

- Mandritto

- Manner of making cuts

- (1) From the shoulder

- (2) From the elbow

- (3) From the wrist

- (4) From the shoulder, but keeping the arm straight and the point forward the whole time

- Fabris’s ranking of methods of making cuts

- (1) is the worst because it’s big and gives your opponent many opportunities to exploit

- (2) is better than (1) because you are less exposed

- (3) is better than (2) because you are less exposed and it’s faster

- (4) is better than (3) on defense because it is faster and your point ends in presence, so you can easily parry or thrust after a cut

- (3) is better than (4) on offense because it is less restricted and freer and, therefore, can more easily deceive the opponent

- When to cut

- Since cuts usually take two Tempi or one long Tempo, they are comparatively easy to exploit and you have to apply them carefully

- If your opponent is waiting, is it better to feint a thrust first, then make a cut because a waiting opponent can attack you as you wind up your cut

- If your opponent is already moving, you can feint a cut and then thrust on their parry

- Cutting vs. Thrusting

- The thrust is better in a one on one fight without armour

- Cuts have some merit when in armour

- Cuts are useful when fighting multiple people at once, because the cut causes greater confusion than the thrust and can parry multiple blows at once

- Disadvantages of cutting

- Cuts usually require at least two Tempi (one to raise the arm or otherwise charge the cut, one to come back down)

- Cuts require more strength

- If a cut misses, it brings your sword and body into disorder

- Recovering from a cut is harder

- Cuts have less reach than thrusts

- Fabris doesn’t elaborate on why, but presumably, because…

- The blade is usually not in a straight line with the forearm when cutting

- The part of the blade that cuts effectively is farther back than the point

- Fabris doesn’t elaborate on why, but presumably, because…

- Cuts are less deadly than thrusts

- The thrust is better in a one on one fight without armour

- The four cuts

- Chapter 8: On good and false parrying, and on some who, with the sword alone, parry with the left arm

- With the sword alone, it is always better to let a thrust pass instead of parrying if you can

- With the sword and dagger, it is easier to defend with one weapon and hit with the other, making defense easier

- “He who does not wish to be hit is forced to parry.”

- Although letting an attack miss is better than parrying, parrying is better than getting hit

- When the opponent is forced to either parry or be hit, we say that the opponent is “in obedience”

- This is a moment of safety in which we can attack the line being opened by the opponent’s defense

- Because being in obedience leaves the fencer vulnerable, we want to avoid being in obedience ourselves

- It is necessary for a parry to contain defensive as well as offensive character in order for a parry to not lead to being in obedience

- How to parrying against a cut:

- “Give the opposition with your forte where the adversary’s sword is about to fall, and at the same time drive the point in with great swiftness, in order that it may arrive before your adversary’s falls”

- “This is an excellent rule, because the cut is shorter than the thrust”

- “If you see that you cannot arrive with a time thrust, there is no need to parry, for it follows that your adversary cannot reach. If you are in doubt, you can withdraw the body a little and let his sword fall, and hit at the end of its fall.”

- There are two reasons why you might not be able to arrive with a thrust:

- The opponent is too far away to reach with a thrust in which case (if we agree with Fabris that the cut is shorter than the thrust) the cut cannot reach us

- We are too close to our opponent to thrust (although I don’t believe Fabris is referring to this situation here)

- There are two reasons why you might not be able to arrive with a thrust:

- “If you wish to parry knowing that you cannot hit, you must still carry your point as if you meant to hit, as this prevents the adversary from changing his line.”

- At narrow distance, you can hit with a thrust before the opponent’s cut falls

- If your opponent cuts first at your sword to clear it, you can treat that as the exact same situation as a beat as discussed in chapter 6

- That is, avoid the beat and hit

- “Give the opposition with your forte where the adversary’s sword is about to fall, and at the same time drive the point in with great swiftness, in order that it may arrive before your adversary’s falls”

- How to parry against a thrust:

- Less strength is required against a thrust, but “more subtlety and ingenuity”

- Thrusts have all the advantages discussed previously

- Thrusts can easily and quickly avoid parries

- It often happens that your opponent moves out of the line while attacking with a thrust such that even if you keep your point on line while parrying, your point goes past the opponent as they change their attack to a new line

- In contrast to the defense against the cut, Fabris does not seem to think that a time thrust is always possible against a thrust

- The most effective defense combines a small movement of the sword with a small movement of the body at the same time (partially voiding and partially parrying)

- “This defence is…

- quicker,

- disorders the sword less, and

- deprives the adversary of the advantage of changing his line”

- “This defence is…

- Less strength is required against a thrust, but “more subtlety and ingenuity”

- Using the non-dominant hand to defend when no secondary weapon is present

- Fabris is skeptical of blade grabs

- He writes that he thinks blade grabs without gloves are a bad idea

- He writes that we should only go for a grab if we can reach the opponent’s hilt or are close enough to come to grips and wrestle

- However, he does not suggest seeking out this situation and instead says that is sometimes simply emerges by accident

- Interestingly, he says that the greatest danger has passed once we are close enough to grapple

- Presumably because we are past the opponent’s point and also too close for the opponent to effectively cut with the sword

- Against people who rely on their non-dominant hand for defence:

- Keep your point a bit high, but not so high that you cannot bring it on line in time in the event of an opponent’s attack

- When you attack, attack on an oblique line

- It isn’t clear to me from the text alone whether the thrust or the footwork is oblique – this is probably made clearer in the plays later

- In wide distance, you can use various feints depending on the initial position of his hand

- In narrow distance, you can hit him before he can find your sword with his offhand

- People who rely on the non-dominant hand are often easier to hit because they keep their sword withdrawn and, as such, do not seek positional advantages with their sword

- Fabris recommends we use the empty non-dominant hand as a supplement to our defenses with the sword

- “When your adversary is about to hit, you must parry with the sword and hit, but it is good at the time of doing this to carry the hand to that part, where his sword might hit, so that the hand will defend the body and exclude the adversary’s sword without a beat. This is a good principle on every occasion when there is time.”

- Fabris is skeptical of blade grabs

- With the sword alone, it is always better to let a thrust pass instead of parrying if you can

- Chapter 9: Engaging the sword. How it is done and when completed.

- Definition of engaging the sword:

- “To engage the sword is to gain an advantage over it”

- This is a kind of counter-position, but it does not completely close the line from the opponent’s point to your body

- The idea is that you cross your opponent’s sword with your own such that…

- it is easy for you to parry a direct attack

- but not equally easy for your opponent to control your sword

- How to engage the opponent’s sword:

- Direct your point towards his blade

- Place the fourth part of your blade across the fourth part of his blade (with a little more of your forth than his) as close as possible without actually touching it

- The sword is strongest in the line in which the point is directed; carry your body and sword in such a way that their strength is in the same direction

- Be careful to keep the point of your sword far enough away from his sword that he does not have the time to push forward with a stronger part of his sword and control your point

- “You must move at the same time as he moves, otherwise you might be hit”

- Engaging the opponent’s sword without touching it has advantages:

- If you do not make contact between the blades, the opponent often does not realise that you have an advantage

- If you make contact with the opponent’s sword, he often disengages, retreats or changes his guard to free himself

- If you make contact with your opponent’s sword and there is any pressure between the swords, a disengage or a yielding action might take your blade out of presence

- “If you keep your sword suspended, it is the more ready for every opportunity”

- My reading of this passage suggests that “engagement” does not necessarily mean “bind” since the swords may not actually be touching

- Things your opponent might do to mess up your engagement:

- He might push his sword forward so that his forte engages your debole

- To prevent this, you should keep the point of your sword far enough away from his sword while engaging that he does not have time to do this

- He might angle his sword point towards your engagement, giving himself the advantage you were seeking

- If this happens, do not attack into his action because you will probably get hit!

- He might move his body away from the line into which your point is directed while you are engaging; if your point is then sufficiently out of presence, he could pass forwards and hit you before you can bring your point back into presence

- To prevent this, do the following:

- Consider the distance between your bodies

- Move forward to engage his sword, carrying your sword without constraint so as to be free to abandon your first plan

- When engaging on your inside: As the opponent moves his body to your outside, bring your forte where you intended to put your point and hit the opponent as he passes forward

- When engaging on your outside: As the opponent moves his body to your inside, bring your forte where you intended to put your point and drop your point below his sword to the outside and hit the opponent as he passes forward

- “In endeavouring to acquire the advantage over the adversary’s sword you must take care not to advance the point so far in your desire to be the stronger, that he can pass in one line or another, before you can direct your point”

- In other words: although you direct your point towards the line your opponent is threatening, don’t take your point so far out of presence that it not longer poses a legitimate threat

- To prevent this, do the following:

- He might push his sword forward so that his forte engages your debole

- What to do if your opponent attempts to engage your sword

- “When then you advance to engage your adversary’s sword and he moves to meet you at the same time, the one who first yields with the sword and drives on to the body, can hit before the other touches swords, or in the same instant”

- If your opponent tries to engage your sword, you can drop the point towards the ground to avoid the engagement

- If he follows your sword down with his, you can thrust while his sword is falling

- Summary

- “If you observe these rules you will without doubt gain the control of your adversary’s sword, which is the first part of victory. Though your adversary takes advantage of the time he will still be hit. To prevent your getting this advantage he will have to retreat, changing the position of his body and sword and to adopt new devices, which are countless. The one who is more subtle in his movements will maintain his sword the freer.”

- Definition of engaging the sword:

- Chapter 10: On time and counter-time, which are good and which false. How to deceive the feint of a time, offered by the adversary so that he may make a counter-time.

- Definition of Tempo or “Time”:

- “A movement made by the adversary within distance is called a tempo.”

- Whatever is done out of distance is simply a movement, not a tempo

- Core principles of Tempo:

- “The time employed to make one movement cannot be employed to make any other”; it is not possible to make two movements at the same time

- The time necessary for your attack must be no longer than the time given by your opponent; otherwise, your opponent will be able to parry your attack

- It is important for a fencer to “correctly estimate motion”

- Definition of an “Attack in Tempo“:

- An attack in tempo is an attack derived from observing a movement of your opponent where the time of his movement is greater than or equal to the estimated time of your attack

- When can one perform an attack in tempo?

- Misura Larga:

- When the opponent makes a motion of the foot

- When your opponent gives you a tempo without realising it

- Misura Stretta:

- Any movement of your opponent that does not bring your opponent away from you

- “in the misura stretta, it is never good to be the first to move unless this move is an attack”

- Misura Larga:

- When is a Tempo not necessary to safely attack?

- In misura stretta, it is possible to safely attack without waiting for a tempo if you are in a counter-posture and need a smaller motion to hit than your opponent needs to parry

- Why?

- Because the direct line is unavailable to your opponent

- Because your attack will arrive before he can change lines

- Why?

- In misura stretta, it is possible to safely attack without waiting for a tempo if you are in a counter-posture and need a smaller motion to hit than your opponent needs to parry

- Definition of Countertempo:

- When you (safely) hit your opponent during their own attack

- When is Countertempo possible?

- When you deliberately make a tempo to lure your opponent to attack, but in such a way that you parry and hit against this provoked attack

- That is, when your opponent’s attack happened on your terms

- When you deliberately make a tempo to lure your opponent to attack, but in such a way that you parry and hit against this provoked attack

- When does Countertempo fail?

- Countertempo actions can result in both fencers getting wounded at the same time. This happens when:

- one of the two has not correctly judged their contratempo

- the one who made the first tempo to invite an attack was too close to the opponent

- the person who made the first tempo made too wide a movement

- Countertempo actions can result in both fencers getting wounded at the same time. This happens when:

- Definition of Tempo or “Time”:

- Chapter 11: On the Cavazione

- Terms:

- Disengage

- Counter-Disengage

- Double-Disengage

- Half-disengage

- Re-engage

- Definitions of terms:

- Cavazione di tempo (disengagement in time): “when your opponent moves to find or beat your sword and you move your blade to the other side of his before he can accomplish his goal”

- Contracavazione (counter-disengagement): when you make a cavazione in the tempo of your opponent’s cavazione, “following his sword according to your original motion to find it”

- Ricavazione (double disengagement): When one who performs a cavazione performs a second one when the opponent counter-disengages in order to cancel out the opponent’s counter-disengagement

- Half-Cavazione (half-disengagement): When you do not disengage all the way to the other side of the opponent’s sword, but stop under it

- Re-engagement: When you start a cavazione then willingly return to the original side as you see your opponent move towards your body or your sword

- Using the disengage

- Offensive: Use a forward oval motion so that at the end of the disengage you have finished your thrust and hit (otherwise, you might not hit in time)

- Defensive: If your opponent comes to find your sword without moving his feet, use a disengage to find his sword

- If your opponent attacks by means of a counter-disengage in the tempo of your disengage, you still have time to disengage again and hit

- Counter-offensive: If your opponent comes to find your sword without moving his feet in order to provoke a disengage and then wound you in a straight line before the end of your disengage, you should re-engage your sword, placing your strong against their weak and thrust

- Using the half-disengage

- Usually used when “you sense that your opponent may make it past your point before the end of the disengage, thus leaving your point out of presence and unable to wound”

- Seldom an initial action, but rather a second or third depending on the distance

- Terms:

- Chapter 12: What feints are and why they are so named

- Definition of a feint:

- “A feint is when you show your opponent that you are attacking one target and you then attack another in the tempo of his attempted parry.”

- Bad ways of feinting

- Stomping on the ground to make a big noise and startle the opponent

- Fabris advises against doing this for a couple reasons:

- It only works if the floor makes a loud noise when you stomp

- An experienced opponent will either ignore the stomp if done out of measure, or exploit the tempo of your stomp if you are within measure

- Fabris advises against doing this for a couple reasons:

- Moving the body and sword forward, but keeping the sword somewhat withdrawn so that your opponent’s parry misses

- Fabris writes that this will only work against a timid or inexperienced opponent

- An experienced opponent will see that your sword is not a real threat and either wound you or perform a counterfeint in the tempo of your feint

- Extending your sword forward, then pulling it back to avoid the opponent’s parry, then pushing it back forward again

- Fabris says this manner of feinting is worse than the other two because, instead of making one motion, you perform three motions – all of which involve a change of direction!

- (1) Extend

- (2) Withdraw

- (3) Extend again

- Fabris says this manner of feinting is worse than the other two because, instead of making one motion, you perform three motions – all of which involve a change of direction!

- Stomping on the ground to make a big noise and startle the opponent

- How to feint properly

- Extend the sword forward…

- …such that, if the opponent allows you to penetrate their defenses enough, you should be in a position to resist their parry with your forte and hit them anyway

- …if the opponent moves to parry in time, you then switch the line of attack while maintaining the forward motion of the sword, and hit before your opponent’s parry is completed

- …if the opponent counterattacks, you must be prepared to defend.

- Always be ready for a counterattack and you will be more alert even if the counterattack never happens

- The initial target of a feint should be a near opening

- If you threaten a target you cannot realistically reach, you will put yourself at risk for nothing

- If you can, feint during the tempo of your opponent

- If you feint while the opponent is moving, he will probably take the feint more seriously because it has the timing of a counterattack

- Extend the sword forward…

- Definition of an invitation

- “An invitation is a type of feint where you willingly offer an opening to the opponent within the measures, giving him an opportunity to strike you there.”

- How to properly give an invitation

- You must correctly judge the distance so that you know the opponent cannot reach you before your invitation is completed

- Be able to judge how best to react to you opponent taking the invitation:

- Either step forwards and counter, or

- Step back to give yourself time to parry and counter

- Do not move your feet during an invitation!

- If you do, then you will not be able to move forward or backwards as appropriate!

- You can shift your body towards or away from the opponent

- The body moves quickly, so you can play with leans

- The feet remain ready to step if needed

- Invitations work best against an opponent who looks impatient to attack

- Hide your intentions

- If the invitation is correctly assessed by your opponent, you have – by definition – given your opponent a tempo

- Give and take

- “If you are sensing that the opponent has something in mind in the way of an attack, it is better to go along with his design and make him fail rather than to not allow him to perform it. In other words, it is better to know what to expect rather than wait for something unforeseen and be wounded without knowing how or why. But it is equally important to know how to oppose his design, in order to wound him and save yourself as he tries to carry it out.”

- Definition of a feint:

- Chapter 13: What is a firm-footed attack and what is a pass

- Definition of a firm-footed attack

- When you attack either by lunging forward with your lead leg or just by leaning the body forward without stepping

- Definition of a pass

- When you attack by moving forward with both feet (usually beginning by passing the rear foot in front of the front foot)

- Comments on the firm-footed attack

- It is the most commonly used attack in duels

- It requires a lot of practice, but – if mastered – will give you a good sense of distance and allow you to make longer than average and accurate thrusts

- Advice for delivering the firm-footed attack

- Start with your dominant leg forward (right leg for right-handers

- Begin with your feet not too far apart

- Put your weight more on your back leg

- Accompany your lunge with a forward lean of the body, to get more reach, but immediately withdraw the body back into safety after attacking

- After lunging, it is a good idea to withdraw the front foot all the way behind the back foot, then take another step back so that your dominant foot is the front one once more

- In this way you will put a lot of distance between you and your opponent after your attack

- Alternatively, you can simple pull your front foot back near your rear foot after your lunge and so be prepared to lunge again or retreat as needed

- Advantages of passing

- It confuses and unsettles the opponent and shows courage

- It causes the sword to arrive with more impetus

- You can easily switch lines while passing

- Once your body has moved past your opponent’s point, he will not be able to wound you

- The person who passes is mor ready to take new initiatives whereas the opponent will be on the defensive

- You can do other techniques that are not possible with the firm-footed attack (like turns and voids)

- Advice for passing

- When you pass your non-dominant foot forward (left for right-handers), keep your dominant shoulder forward (right for right-handers)

- This ensures your maximum reach

- This also results in a voiding action

- Continue passing all the way to the opponent’s body

- When you pass your non-dominant foot forward (left for right-handers), keep your dominant shoulder forward (right for right-handers)

- Definition of “passing all the way to the body”

- Passing past the point of your opponent’s weapon and continuing until you are against their body

- Usefulness of “passing all the way to the body”

- Sometimes, it is impossible to recover backwards after an attack without being wounded; in this case passing forwards to the body is safer than trying to withdraw

- Once you are past the opponent’s point, they need to withdraw their sword before they can wound you and you can use that time to your advantage

- As you pass all the way to the opponent’s body, you can do things that give you an advantage:

- You can unsettle him by bumping into him with your body and then grabbing his sword by the hilt

- You can wrestle the opponent and throw him to the ground

- If you have already stabbed your opponent, your blade will pass all the way through his body and your hilt punch into his chest, further shocking him

- However, if your opponent is fighting with sword and dagger, getting past the sword’s point still leaves you vulnerable to the opponent’s dagger

- There are still things you can do, but this will be discussed later in the sword and dagger section

- Advice for how to stand in guard

- You should generally stand with your dominant foot forward (your right foot for right-handers)

- If you are on guard with your non-dominant foot forward, your reach is shorter unless you pass with your attack, but even then the attack with the pass is larger, slower, and leaves less opportunity to recover

- With your dominant foot forward, you can both attack and withdraw quickly, because your feet and body make a smaller motion

- The only good reason to stand with the non-dominant foot forward is if you are waiting for the opponent to attack

- Once the opponent attacks, you pass backwards with a single time parry and counterattack

- You should never take the initiative and go on the offensive with your non-dominant foot forward

- A guard with the non-dominant foot forward is more useful if you have an off-hand weapon like a dagger

- You should generally stand with your dominant foot forward (your right foot for right-handers)

- Summary

- There are two basic kinds of attacks:

- Firm-footed attacks

- Passing attacks

- Advantages of firm-footed attack:

- Smaller step

- Faster

- Easier to recover from

- Advantages of the passing attack:

- More momentum

- More assertive

- Gets you past your opponent’s point faster

- There are two basic kinds of attacks:

- Definition of a firm-footed attack

- Chapter 14: On holding the sword extended, straight, angled, or withdrawn

- There are three basic ways that people hold the sword in guard:

- Sword angled

- Sword is held at an angle to the forearm

- Arm withdrawn, with the hand held near the knee

- Sword in line with the elbow

- Sword is held in line with the forearm so that it forms straight line from the elbow to the point of the sword

- Arms is withdrawn

- Sword extended as much as possible

- Sword held in line with the arm so that it forms a straight line from the shoulder to the point of the sword

- Arm is extended as much as possible

- Sword angled

- Each of these positions has advantages and disadvantages

- Sword angled

- Advantages

- The sword is stronger (harder to displace)

- It is easier to keep your sword free (because it is withdrawn)

- Disadvantages

- Cannot make small blade actions well

- Offers larger openings

- Parries require large movements

- Vulnerable to opponents who know how to attack on a straight line through your debole

- Advantages

- Sword in line with the elbow

- Advantages

- Good compromise position

- You can attack and defend well

- You can do small blade actions

- You can seek advantageous engagements

- you can keep your point in line easily

- Because the arm is withdrawn, it is easier to keep your sword free

- Less tiring than a fully extended arm

- It is harder for the opponent to attack under your arm

- Good compromise position

- Disadvantages

- It is a compromise, so you miss out on the advantages of the extremes

- Advantages

- Sword extended as much as possible

- Advantages

- Keeps the opponent far away

- Opponent must displace your point before they can attack you

- It is easy to parry from this position – especially against cuts – because you only need a small motion to parry

- Your openings are smaller

- If he tries to wound you under your sword, it is easy to wound him from above

- Disadvantages

- Holding the sword this way is fatiguing

- Even a small movement can bring your sword out of line and give your opponent an opportunity to get past your point

- Your sword arm is vulnerable, because it is extended forward

- It is harder to keep your sword free (because you are offering it to your opponent)

- Advantages

- Sword angled

- Specific advice for sword extended as much as possible

- Keep your stance narrow

- This keeps the lower parts of your body (which are most vulnerable in this position) as far away as possible

- The more narrow your stance, the wider you can lunge forward or retreat backwards

- Keep the opponent at a distance

- If the opponent can get past your point, he can pass all the way to your body

- Your sword arm is the most vulnerable target, but you should defend it with small blade motions always remaining in line

- You must learn to lunge without flinging the arm, using only your legs and body to adjust distance

- You must always work to keep your sword free but also close to the opponent

- Keep your stance narrow

- Fabris admits some advantages of the angled guard, but does not seem to recommend it

- Fabris says you should use all three of these ways of holding the sword as the situation demands

- However, he also says the best way to hold your sword:

- “In order to be safest of all, you should hold your sword arm not quite extended, but more extended than not, with the sword directed straight toward the opponent or just out of line as the opponent’s posture calls for”

- This position has the following advantages:

- Arm mostly extended, so defenses require only a small motion

- Not as fatiguing as a full extension

- Slight bend in the arm makes it stronger

- Easier to keep your sword free than when fully extended

- Harder for your opponent to sneak an attack under your arm

- A good fencer needs to be able recognise how their opponent is standing and know what the opponent can do from that position

- “Remember, even though one stance may be better than another, all of them have shortcomings”

- There are three basic ways that people hold the sword in guard:

- Chapter 15: On how to keep the body whether it is better to keep it high or low

- There are two basic ways of standing:

- Upright and straight

- Low and bent

- It is better to stand in a low and bent posture than an upright and straight one

- Defending an upright body requires larger motions

- You can cover more of your body with your forte in a bent posture, meaning your forte does not need to travel as far to protect you

- If you attempt a deep lunge from an upright posture, you have to bend your body anyway and, as you bend it, your movement is so long that you probably won’t recover in time

- If you stand up straight, “you will be more disunited and less strong in body and sword”

- Defending an upright body requires larger motions

- However, a posture you are comfortable with will serve you better than a posture you find awkward

- “If you know how to carry your body forward properly and without awkwardness, you will be better served if you were to bend it. But if you think you cannot, you should rather remain straight, because if you force your posture you will never be as ready to move.”

- It takes practice and hard work to learn to fence in a low and bent posture, but the benefits are worth it

- “In order to learn how to properly keep your body low in this manner, you will need a fair amount of practice and hard work. But afterwards, you will be quicker, more comfortable, more ready, and, most importantly, safer; you will be able to defend without fumbling and wound faster and from farther away. Since your body is already bent, you will be able to forward without making a large motion.”

- “The fatigue you will experience while practicing this stance will be considerably less than the benefits you will enjoy from it. We are talking about defending not only your life, but also your honor in one stroke. The person who can deport himself with more caution and confidence is worth of more praise and will receive more tribute. For sometimes, a small advantage can lead to a great victory.”

- Advice on how to stand in a low and bent posture

- Bend your upper body at the waist

- Put your weight on one foot at a time

- The unweighted leg will be freer to move

- There are two basic ways of standing:

- Chapter 16: Some advice for when you face a tall, a short, a weak, a strong, a hot-tempered, or a cool-headed opponent

- You should size up your opponent immediately at the start of each bout

- What is your opponent’s…

- style?

- strength?

- size?

- What is your opponent’s…

- If you are tall and your opponent is short:

- Focus on exploiting your greater reach

- Keep your sword free

- Keep your opponent at a distance

- Retreat after your attacks to keep your distance

- Do not use passing attacks, because these collapse distance relatively quickly

- Against passing attacks, bring your body out of the way and retreat while presenting the point

- If your opponent comes to you, wound him when he enters your range, but is not yet close enough to reach you

- If your opponent will not come to you, proceed with caution but retreat whenever he tries to approach to frustrate his plan of attack

- “You should keep this game up until he finally gives you a good opportunity to either wound him or to put him into obedience”

- Focus on exploiting your greater reach

- If you are short and your opponent is tall:

- Your only advantage is that you need smaller movements to protect yourself

- Your best bet is to wait and find your opponent’s sword, so that he cannot wound you while you enter into measure

- Once you have entered measure and found the right tempo to attack, you should attack with a pass to get past the opponent’s point as quickly as possible

- Once past the opponent’s point, you have an advantage

- As the shorter fencer, it is critical to know how to control distance

- If you are strong and your opponent is weak

- You are at a great advantage!

- You should base your strategy on finding the opponent’s sword because you can win blade engagements more easily

- Sometimes the stronger part of your debole will prove stronger than the weaker part of the opponent’s forte

- However, the strongest part of his forte will still be stronger than the weakest part of your debole

- Sometimes the stronger part of your debole will prove stronger than the weaker part of the opponent’s forte

- When you find your opponent’s sword, you will make him move and you can wound him or find his sword again

- Firm-footed and passing attacks are good for you

- If a passing attack leads to wrestling, all the better since the stronger person has an advantage in wrestling

- If you are weaker than your opponent

- Do not let the opponent find your sword

- Avoid parrying entirely if you can avoid it

- Keep your opponent at a distance

- All of your defences are best accompanied with a slight withdrawing of the body

- You should try to interrupt cuts, however

- Do not shorten the distance, instead entice your opponent to attack by offering him a tempo or pretending to let him find your sword

- “If he falls for it and starts an attack, break measure just a little and situate your point against the opening he will have created: as he comes forward, he will stab himself.”

- Keep your point on him to dissuade him from passing

- “For all these reasons, it is evident that a weaker person should not aggressively attack a stronger one, but should rather paly the waiting game and rely on the advantage of the distance.”

- If your opponent is hot-headed or short-tempered

- Provoke him to attack and wound him as he comes in

- “It would not be good to go against him, as in the short play or at wrestling you would lose the advantage of the point of your sword. Instead, you should try and augment his fury in order to cause him to make a mistake, at which point (depending on the occasion) you can either meet him with a thrust or withdraw and wound him with a one-tempo parry and counter before he passes.”

- If your opponent is cool-headed and calmly waits in his guard

- It is good to attack him, but you need to be careful not to be deceived

- Often you might think your opponent’s only concern is to defend, but instead you end up being wounded

- No matter who your opponent is, “you should never underestimate him, but rather always be cautious and ready for whatever may come so you can be prepared for everything.”

- You should size up your opponent immediately at the start of each bout

- Chapter 17: General discourse on the guards

- This chapter is a short preface for the subsequent illustrations that examine the guards and various example techniques

- “First of all, let me warn you not to be puzzled at seeing two figures in every drawing, each doing the same thing. This has been done in order to show the body from both the right and left sides.”

- Fabris mentions that he has deliberately omitted many guards that other people talk about

- “All these things I have omitted as non-pertinent and actually more counter-productive than anything. It may have even been better not to mention them at all, in order to spare my reader some tedium, but I have chosen to touch upon them so that I may not be accused of not having carefully examined them.”

- A few things Fabris thinks are generally a waste of time:

- Guards that hold the sword withdrawn and low so that the point is near the feet

- Guards that hold the sword sideways

- Guards that hold the sword behind the back

- Grabbing the blade of the sword with your off-hand to fortify your sword and beat away attacks

- Disarming the opponent with your sword

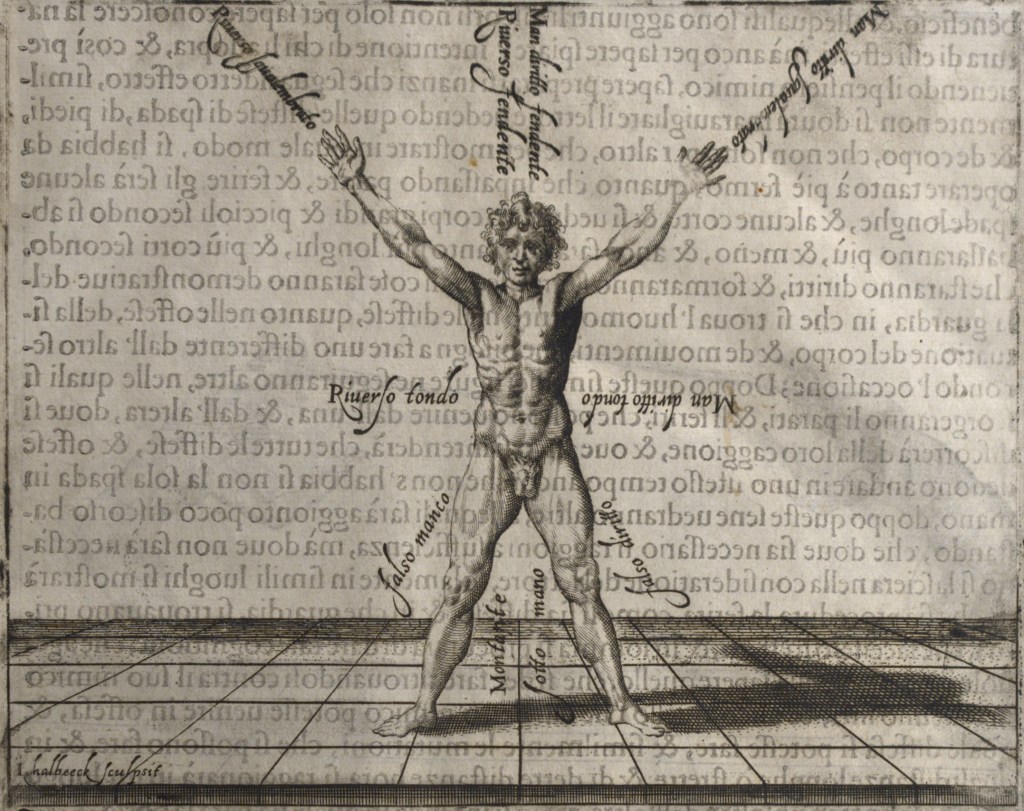

- Chapter 18: On the illustration showing the nature of the cuts and where they strike

- This chapter is very short and just shows an illustration will the names of various kinds of cuts

- Fabris writes: “Even though I have not touched upon the differences between all these cuts, I think that I have discussed all that is necessary for our purpose in previous chapters. I will instead move on to more important and useful matters.”

- Recall from earlier chapters that Fabris doesn’t have a very high opinion of cuts

Selected Quotations

This is just a collection of quotations that I either liked or thought were particularly important.

“The discourses will be such that you will easily see when to apply the various rules, and how to the best advantage you must approach your adversary in order to come within presence. Though one who understands the art may approach as he pleases, since in whatever position he is, he will succeed by his knowledge of distances, weak and strong positions, exposed and unexposed parts.”

– Book 1, Chapter 1

“In short, if you wish to get within distance with some safety, you must first form the counter-position, and if disconcerted by your adversary’s counter-position, it will be better to break ground than to approach, until there is an opportunity to get an advantage.”

– Book 1, Chapter 4

“You are within wide distance when by advancing the rear foot to the front you can make a hit.”

– Book 1, Chapter 5

…

“In [close] distance you can reach with the sword by merely bending the body, without moving the feet”

“If you are within wide distance and wish to advance within close distance, the danger is greater when the adversary stands steady on his guard, because if you raise your foot to advance it, you give him an opportunity to hit and retire, so that at the end of the movement you would be at the same distance, that is wide distance, and would have obtained nothing. All this is due to the fact that you cannot move your foot in less than two times, the one in lifting it and the other in putting it to the ground. For this reason some push the foot forward by scraping it along the ground, which is well enough in the hall, but in the street is likely to lead to a fall because of the many unevennesses. It is better then to lift it to make sure of not stumbling.”

– Book 1, Chapter 5

“When you are within wide distance and your adversary makes some movement of his foot, provided he does not break ground, you can hit him in the nearest exposed part, even if he has not moved his weapons. This could not be done if he moved his weapons and stood firm on his feet, the reason being that a movement of the foot is slower than that of the weapons, and therefore he could parry before your sword arrived, while he remained steady; if there were no other way he could protect himself by breaking ground, so that your sword could not reach. Being thrown into disorder you would then be in danger of being hit before you had recovered. Therefore whenever he gives an opportunity without moving his feet, it would be better to approach within close distance in that time.”

– Book 1, Chapter 5

“If the opponent keeps breaking the measure as you try to gain it, never get impatient and follow him. Actually, this is where you have to be careful, because there are many who feign retreat with the precise intent of enticing the opponent to follow and wound him in the tempo thus created. Instead, remain calm and maintain your form. This will actually give the opponent a sense of false security, which will cause him to come forward: as he does so, he can be wounded in that tempo and will not be able to save himself.”

– Book 1, Chapter 5

“He who does not wish to be hit is forced to parry.”

– Book 1, Chapter 8

“Many things we omit for the sake of brevity, as our purpose is to deal with fundamental principles only, from which can be deduced countless rules, some better than others; for this subject is so large that it is difficult to find an end.”

– Book 1, Chapter 8

“To engage the sword is to gain an advantage over it; it is a kind of counter-position with some difference, because often you have engaged, the adversary’s sword without completely closing the line from his point to your body. But it has this advantage, that your adversary cannot hit without passing your forte, which is so near his point, that you can find the point while he is moving to make the lunge. The counter-position is not considered well formed except when the line from his point to your body is fully defended. But the same advantage may be obtained by relative strength, so that you are considered to have engaged, when you are sure that your sword is stronger than the adversary’s and cannot be pushed aside, but can push his aside”

– Book 1, Chapter 9

“You must bear in mind that the sword is always stronger in the line in which the point is directed, and in order to advance in that line you must know how to carry your body and sword in such a way that their strength is in the same direction”

– Book 1, Chapter 9

“In endeavouring to acquire the advantage over the adversary’s sword you must take care not to advance the point so far in your desire to be the stronger, that he can pass in one line or another, before you can direct your point. If you observe these rules you will without doubt gain the control of your adversary’s sword, which is the first part of victory. Though your adversary takes advantage of the time he will still be hit. To prevent your getting this advantage he will have to retreat, changing the position of his body and sword and to adopt new devices, which are countless. The one who is more subtle in his movements will maintain his sword the freer.”

– Book 1, Chapter 9

“If you operate according to the above rules, you will be able to find the opponent’s sword, which is the first part of victory. If the opponent, at this point, tries to take advantage of the tempo that you make when you find his sword, he will certainly be wounded. If he does not wish you to gain such an advantage over him, he will have to withdraw and change the posture of his body and sword, and adopt one of the other virtually infinite tactics.

– Book 1, Chapter 9

He who is subtler in his movements will always be able to keep his sword more free.”

“I hope that I have conveyed how dangerous it is to approach an opponent haphazardly, without some prior advantage – especially in the misura stretta.”

– Book 1, Chapter 10

“If you wish for your feints to succeed, you should push your sword forward in a such a way that, if the opponent allows it to penetrate enough, you have the certainty that you are able to resist his parry on your forte. In order for this to happen, you must maintain the sword’s forward motion, thus not giving the opponent time to parry and wounding him.

– Book 1, Chapter 12

If your opponent moves just in time for the parry, you should then switch the line of the attack, while still maintaining the forward motion of the sword, thus arriving on target before he finishes his parry. This is the correct way to perform feints.

As you perform the feint, it is always vital to be ready for a counterattack. If you take for granted that you will get to your opponent before he can get to you, you will soon be deceived. Instead, be always expecting a counter, you will be more ready to defend: and even if the counter never arrives, you will be more alert and your action will be made easier.”

“If you are sensing that the opponent has something in mind in the way of an attack, it is better to go along with his design and make him fail rather than to not allow him to perform it. In other words, it is better to know what to expect rather than wait for something unforeseen and be wounded without knowing how or why. But it is equally important to know how to oppose his design, in order to wound him and save yourself as he tries to carry it out.”

– Book 1, Chapter 12

“It sometimes happens that as you perform a firm-footed attack, you carry yourself so far forward (either because you have underestimated the distance or because your opponent lunges too) that it is virtually impossible to step back out of distance without being wounded. In this case it is good to pass all the way to the opponent’s body: the greater danger is when you enter the measures, but when you go past the opponent’s point as you pass, you have a good chance to defeat him before he can withdraw his sword and wound you.”

– Book 1, Chapter 13

“There are some who, even if you pass all the way, manage to withdraw just enough to wound you, something that is even easier with a short sword than with a long one. However, I insist that if you know how to pass all the way to the opponent’s body, you will be safe no matter the length of his sword.”

– Book 1, Chapter 13

“If you pass, you can also wrestle the opponent and throw him to the ground, which would be ideal if your sword has not landed on target. Undoubtedly, if your sword did land on target while passing, it would penetrate your opponent’s body all the way to the hilt, which would further punch and shock your opponent. In addition, the wound that you would so inflict would be disabling enough that the opponent will not have the resources to pull his sword back and wound you.”

– Book 1, Chapter 13

“In conclusion, knowing how to perform a firm-footed attack is one thing; knowing how to execute a pass is another. And with the joint knowledge of these techniques you will be able to successfully operate according to who your opponent is and what tempi he offers you. Sometimes, in fact, you will only be able to execute a firm-footed attack for the brevity of the tempo offered you.”

– Book 1, Chapter 13

“Always remember that a single technique is never effective in all situations, but that each has its specific purpose, and one that is good for one occasion may not be so good for another. As I have already mentioned, you should have a rich repertoire and carefully select the technique that is most appropriate for the specific situation.”

– Book 1, Chapter 14

“If you know how to carry your body forward properly and without awkwardness, you will be better served if you were to bend it. But if you think you cannot, you should rather remain straight, because if you force your posture you will never be as ready to move.”

– Book 1, Chapter 15

“If you are the weaker of the two, you should always make sure that your opponent does not find your sword. Never parry if your opponent attacks, because his debole may actually be stronger than your forte, and you will deceive yourself in believing that you can defend with it. A different case would be where the strongest part of your forte goes against the weakest part of his debole, in which instance the advantage is such that even one had can prevail against two.”

– Book 1, Chapter 16

“It is always imperative to consider the dangers you may incur, no matter what the nature of your opponent. And you should never underestimate him, but rather always be cautious and ready for whatever may come, so you can be prepared for everything.”

– Book 1, Chapter 16

“For example, there are some who consider the disarming of the opponent with your sword to be an essential staple of sword alone. This I believe to be a technique of very little consequence, because it can only succeed against those who have no notion whatsoever of keeping the sword free or of the disengage. Against any other person, it will not only be ineffectual, but it will consistently get you defeated, so we will talk no more of it.”

– Book 1, Chapter 17

Leave a reply to Fabris Overview – Blume des Kampfes Cancel reply